150 years ago on Monday 6th December 1875, a terrible explosion ripped through the underground workings 230 yards beneath the surface at Swaithe Main Colliery, near Worsbrough, near Barnsley. A second explosion had also likely been triggered by the first.

239 men and boys were at work underground at the time, and altogether the disaster claimed 143 lives, although the specific cause was never ascertained.

The explosion killed horses and men, flame burning a number of victims and charring the wooden props, as well as blasting coal tubs (corves) and other debris and causing roof falls blocking parts of the workings. Two of the first rescuers also succombed to afterdamp.

We remember them and the real dangers of working the Barnsley Coal seam in the 19th Century, just as was worked at Hemingfield Colliery, Lundhill and the Oaks which all saw disasters in the 1850s and 1860s.

Peace above, violence below

Swaithe Main Colliery was established in the 1850s as a joint undertaking with Edmunds Main Colliery; indeed the two pits were interlinked underground, which was also the proximate cause of an explosion at Edmunds Main thirteen years earlier, on 8th December 1862, causing 59 deaths. The underground link of 1862 between Swaithe and Edmunds Main would provide an escape route for many of the survivors of the explosions in 1875 who could not safely exit via the winding shaft.

The Edmunds and Swaithe collieries were operated by a co-partnership of Charles Bartholomew (1806-1895), John Tyas (1817-1895) and Joseph Mitchell (1807-1876) which was established initially in 1854 for the commencement of the Edmunds Main Colliery, leasing areas of coal in Worsbrough, Blacker Hill and Dovecliffe, as well as around Swaithe itself slightly later.

Writing in 1871, the area was described as follows:

Worsborough Dale, situate about two miles from Barnsley, may be said to be the heart of the South Yorkshire coal field, for within it and its immediate neighbourhood the well-known and valuable Nine-feet seam has been more extensively worked than in any other part of it. It is true that long chimnies vomiting masses of dark smoke and colliery head-gearing are not the most pleasing adjuncts to a picture, nor do they add much to the beauty of a landscape, yet from the ridge which tops the dale of Worsborough is to be seen some of the most charming scenery to be found in almost any part of Yorkshire, and as such has often furnished material for the works of some of our most eminent artists.

Mining Journal, 7 October 1871, Vol.XLI, No.1885, supplement, p.885

Swaithe Main had a pitch pine timber headgear 56 feet tall, with two winding wheels, 17ft diameter, wound by two 60 Horse Power steam engines, fed by nine boilers. The downcast and winding shaft was 230 yards deep and 13ft 6 inches diameter, and the upcast shaft, some 68 yards away, was 225 yards deep, 12ft 9 inches diameter.

The colliery manager John Mitchell was the son of one of the owners, and developed new appliances to improve the productivity of the pit, including an enclosed furnace underground feeding a chimney 40 yards up the upcast shaft, to try to avoid some of the known dangers of open furnace ventilation in gassy mines.

He also increased the initial coal winding capacity with the introduction of double-decked cages. He oversaw the underviewer James Allan, who dealt with the underground deputies, usually four on the day shift and two on the night shift, i.e. William Midgley and Joseph Sheldon on the 6th December 1875.

‘a noise as of a collision between railway waggons’ – the manager’s view

At the inquest following the disaster, John Mitchell gave straightforward evidence of what he saw:

“I generally went down the pit three or four days, and frequently every-day in a week. Gunpowder for blasting was used with my sanction, except on the slant drift level and slant level.

[…]

On the 6th ultimo, a little before ten o’clock, I had left the office to go to the drawing shaft, a distance of 150 yards, and heard a noise as of a collision between railway waggons. I only heard one sound. William Bellamy, the engine-wright, met me, and I accompanied him to the Pit-hill. Smoke was clearing away when we got there. Out the up-cast shaft smoke more than usual continued to emerge. On trying to move the ropes in the drawing shaft, the cage at the bottom was found to be fast.

One rope was then unfastened, and was clamped to the top, and then I and William Bellamy and Joseph Sheldon went down on the other rope. I saw no damage until we reached the bottom, where the conducting rods were broken off on a level with the top of the porch. About 23 or 24 men were there. Seven or eight of them were injured. There were also three dead bodies…

Copy of the Report of the Swaithe Main Colliery Explosion, House of Commons, 20th March 1876, p.29 (testimony, 13th January 1876)

Investigation and Inquest Verdict

The Chief Inspector for the Yorkshire district, Mr Frank N. Wardell was summoned immediately and recounted arriving at the scene and helping to coordinate the response at the Inquest sessions held in January 1876:

“On the morning of the 6th December last, I received a telegram informing me that a fearful disaster had occurred at Swaith Main Colliery. Hastening there at once, I found, indeed that the report was not exaggerated. After having been made acquainted with the main facts of the explosion, and learnt from those in charge of the operations what they had done, we held a consultation for the purpose of deciding what steps should be taken for the recovery of the bodies and the restoration of the ventilation, and how these matters could be accomplished with the least amount of risk.

It was decided, and very properly in my estimation, to put out the furnace at once. Although the construction of the furnace is such that the return air is not conducted directly over the flame, but passes up the shaft for some distance outside the furnace tube or chimney, yet to prevent any probability of accident, this measure was considered to be advisable.

Upon ascertaining the character and extent of the calamity, I communicated immediately with the Secretary of State, who at once directed that my colleague, Mr. Evans, should assist me in my investigations, and instructed Mr. Maule to attend the inquest, and watch the proceedings on behalf of the Government […]

I feel it my duty to make the following observations with respect to the general discipline of the mine. In the first place, the eighth general rule of the “ Coal Mines Regulation Act, 1872,” expressly enjoins that during three months after any inflammable gas has been found in a mine, powder shall not be taken into or be in the possession, of any person in any mine, except in cartridges, and yet though gas has been reported here for some time previous to the explosion, powder was taken into the mine loose in canisters.

[…]

Feeling so strongly as I do on the question of the use of powder in Barnsley and Silkstone seams, I cannot but advert once again to it. Whether or not it has in this instance primarily led to the explosion, and in my opinion it has not, still the all-importance of the subject is self-evident. It is marvellous to me that owners and managers will, in mines where it is considered necessary to use locked safety lamps, incur the responsibility of allowing powder to be introduced. “

(Copy of the Report of the Swaithe Main Colliery Explosion, House of Commons, 20th March 1876, p.34, covering depositions from 14th January 1875)

Rescue and Recovery

On the 6th, 7th and following days numerous descents continued to explore the workings and endeavour to recover bodies. Colliery managers from nearby pits and numerous volunteers joined in the exploration and recovery work. Two of the initial explorers Jospeh Sheldon (a deputy at Swaithe) and Thomas Kilburn ventured into dangerous parts of the workings and were killed by the effects of afterdamp.

On the first two days some survivors were retrieved, but the following days were largely clearing the workings and restoring ventilation making it safe to recover the remaining victims and further investigate the causes.

Inspector Frank Wardell described these efforts:

“The consultation resulting in the extinction of the furnace, I may say, was followed up by others at short durations of time, for several days, during which the recovery of the bodies proceeded. Parties were organised, who, each under one competent and reliable person, confined their operations to one particular section of the workings, the district of each being clearly defined, as well as the work to be done, and in all cases a written report of the proceedings was handed in at the office at the close of each shift.

Extreme care was used, and every step taken in the work was well considered beforehand, and I add with gratification that, throughout the operations, the manager and engineers present, who took part in the consultations, together with my colleagues and myself, were unanimous, and acted in concert.

The restoration of the ventilation to a sufficient extent to admit of an examination being made of the pit, was a work of some considerable time. Explosive gas and afterdamp had both to be fought against inch by inch, the bodies of the men and the horses being sent out at the same time, but so soon as ever it was practicable, Mr. Evans, Mr. Gerrard, and myself, in company with the manager and others, made an inspection.

(ibid).

Verdict

The Inquest included West Riding Coroner Thomas Taylor, and barrister John Blosset Maule Q.C., Recorder of Leeds. Representative of the South Yorkshire Miens Association were also present. Copious witness testimony was taken, but the jury’s verdict was clear:

“We find that Joseph Sheldon and Thomas Kilburn, on the 6th day of December last, were accidentally suffocated by afterdamp, while searching for persons injured and killed by explosion of firedamp in Swaith Main Colliery, and that James Blackburn, Andrea Konuck, Thomas Bullock, James Burns and the other 137 persons died from the effects of the said explosion, but the evidence is not sufficient to show the cause of such explosion.

And we are of opinion that, according to the evidence, the Swaith Main Colliery is a fiery mine, and that the general and special rules have not been rigidly carried out, and that gunpowder has been recklessly used. We are also of opinion that in all mines where safety lamps are used, the use of gunpowder should not be allowed except in stone drifts, and then only when all the miners are drawn out. And we regret that the miners have not carried out General Rule No. 30, and we think that this Rule should be strictly adhered to.”

Swaithe Main: Impact and consequences

The disaster made national news with over 40 reporters from all over the country heading to the pit, and filing reports via telegraph to share details of the explosion, rescue and participants’ testimony. In the week following the explosion 506 telegrams consisting of 230,201 words were dispatched by members of the press from the Barnsley Post Office telegraph office. The Barnsley Chronicle reported on 18th December 1875 that it had had to increase the print runs to meet demand for between 30 and 40,000 copies as well as additional Royal Mail bags to dispatch the newspaper to agents across the country.

The 143 victims of the disaster included English, Polish and Hungarian miners working at Swaithe Main, the surviving families included 75 widows with 157 children left unprovided for.

Relief funds

There was an immediate response to the disaster to raise a relief fund, as had happened at the Oaks Disaster in 1866. This time there was also an attempt to copy the example of the Northumberland and Durham Relief society and try to establish a Permanent Relief fund consolidating earlier funds.

The Reverend Henry J. Day of Barnsley was a leading figure in this work, although it would take time to agree such an approach, so the initial meeting summoned by the Mayor of Barnsley, Richard Carter sought “to consider the expediency of raising a fund for the relief of the sufferers”. The Swaithe Explosion Fund was established under the secretaryship of Joseph Wilkinson.

This work would, eventually, lead to the establishment of the West Riding Miners Permanent Relief Fund in 1877, whose work will be the subject of further contributions here.

One story: the Banks family

One family story may serve to illustrate the impact of the disaster, that of George Banks. After retrieving his body along with others on Friday 10th December, they were held in the sawing shed and colliery pay room. His brother identified him and signed the notebook of Coroner Thomas Taylor to confirm:

“Charles Banks, of Worsbrough Common, Colliery underground labourer, on his oath, said – The deceased, George Banks, was my brother, 38 years old, and a coal miner. I saw his body at Swaithe Main Colliery last Friday morning. He was burnt about his face, neck, and body. He was in the Free Gardeners’ Club, and the Miners’ Association. Charles Banks.”

George’s body was the 109th to be recovered, he left a widow Sarah Jane (his second wife after his first wife Ellen had died in 1866) and 9 orphaned children, living at Swaithe Row, Mitchell Street, Swaithe.

- Mary (1862-1928)

- Ann (1863-1919)

- Elizabeth (1865-1951)

- Ellen (b.1866)

- Thomas (1868-1930)

- Hannah (1870-1937)

- William Henry (1872-1957)

- Emma (1875-1949)

- Eliza (1875-1962)

The Swaith Main Colliery Explosion Fund was an essential safety net for this large, and in 1875, still young family. More details of the fund, including images of the accounts where Sarah Jane’s name can be seen, are available from Barnsley Archives blog from 2022.

Thanks to George’s descendants (his great-great-grandson Andrew Jones), we know that George and Sarah Jane Banks’ youngest son, William Henry Banks (1872-1957), was orphaned by the disaster at the age of 3.

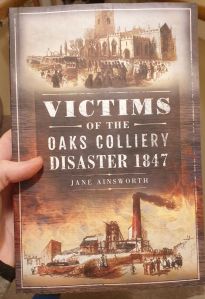

Thanks also to the work of local historian Jane Ainsworth in her recent book Victims of the Oaks Colliery Disaster 1847, we also know that W. H. Banks was actually named after George Banks’ brother of the same name who was killed at Wombwell Main Colliery on 29th September 1865.

George’s son William Henry Banks, himself became a coal miner, serving as a deputy at Strafford Main Collieries (Rob Royd shaft) before becoming a draper and boot dealer at Snape Hill, in Darfield as well as becoming a prominent Methodist Lay Preacher in the Hoyland and Wombwell area circuits for over 50 years.

Poignantly, in his own lifetime, William Henry Banks joined the St John’s Ambulance classes at Strafford Main Colliery, even captaining ambulance teams in local area competitions. He was also involved in the early Mines Rescue training at the Tankersley Joint Rescue Station at Birdwell. He was at the station in Birdwell in 1908 when they dispatched a team to Hamstead Colliery disaster.

During the Second World War he also served as an Air Raid Precautions first aider. After him, none of his children, or descendants became miners again, but remaines proud of their mining heritage and remember the sacrifice of George Banks and so many others 150 years ago.