Terry Hudson and the NCB’S South Yorkshire Mines Drainage Unit – A working life in a vanished industry

Introduction

Steve Grudgings (Chair of FoHC) shares the story of the remarkable working life of Terry Hudson, employed by the Mines Drainage Unit (MDU) for many years.

“If you want to know where footrill was, you need to talk to Terry Hudson down bottom of Westfield Road”.

This was my introduction to Terry from one of his neighbours. I was looking for the remains of the footrill entrance (the local term for sloping walk in entries to coal mines) that gave access to the bottom of Westfield Pumping Shaft at Parkgate, on Rotherham’s northern outskirts.

This trip was part of my research into the network of engine houses and drainage levels that used to be the responsibility of NCB’s South Yorkshire Mines Drainage Unit (MDU hereafter). Terry wasn’t at home when I called, and even when I wrote to him, he wasn’t keen to talk to me – the reasons for which soon became clear.

At the time (2014) I had just been informed the group I was involved with (Friends of Hemingfield Colliery – FOHC for short) had been successful in our bid to purchase one of the MDU’s remaining colliery sites.

After a while, Terry agreed to a recorded oral history interview, and as the somewhat fragmented story of his life unfolded, I became fascinated by the variety of his working experiences, most of which involved the South Yorkshire Coal Industry.

It was clear that, despite leaving school at 15 in 1954 (the year I was born), Terry was a capable practical engineer and had been trusted by his superiors to deal with some difficult and dangerous underground assignments.

I was so taken with his life story, I asked if I could develop it into an account suitable for sharing with a wider audience that might not have detailed engineering or coal mining knowledge.

What follows draws on my conversations with Terry over time. It follows the time sequence of his working life, and dives into the details of those areas I found particularly interesting.

Oral history notes

Some of the questions and prompts used whilst interviewing Terry have been retained in the text, so the full answers that follow make sense. I have added photographs, maps and drawings to illustrate some of the locations and activities described and included details of the sites Terry worked at, and the organisations he worked for.

The interviews were recorded in Terry’s garage, and my stalwart friend Jan Hazelby has done a superb job in interpreting what was said and sorting it into good order.

The text in italics is in Terry’s own words, a direct extract from the transcript of my interviews with him, sometimes grouped or resequenced for continuity of themes, or completeness of timelines.

A sensitivity warning – wherever possible the original direct language used has been left unedited, whether in reported speech or in expressions of personal opinion. If any readers consider them inappropriate or even offensive, please stop reading immediately to save offence.

I hope you find reading this as interesting as I did interviewing Terry.

Terry’s Early Life

I were born on June 21st 1939,at my grandmother’s, Mangham Quarry (Rawmarsh) they called it. It were a row of houses where Ronald’s scrap yard is.

There used to be a row of houses there and I were born at me grandmother’s number 36 Mangham Road, Mangham Quarry, because some called it Quarry some called it Road, but we always called it Road.

They didn’t like quarry being stuck on the end of it. They called it that because if you go past it now Readymix Plant is there, where that plant is now, that was the quarry, and there were a row of houses upside of that quarry, and that’s where I was born, at my grandmother’s and I lived there up to being 19 or 20 and they knocked them all down.

– What did your Mum and Dad do Terry?

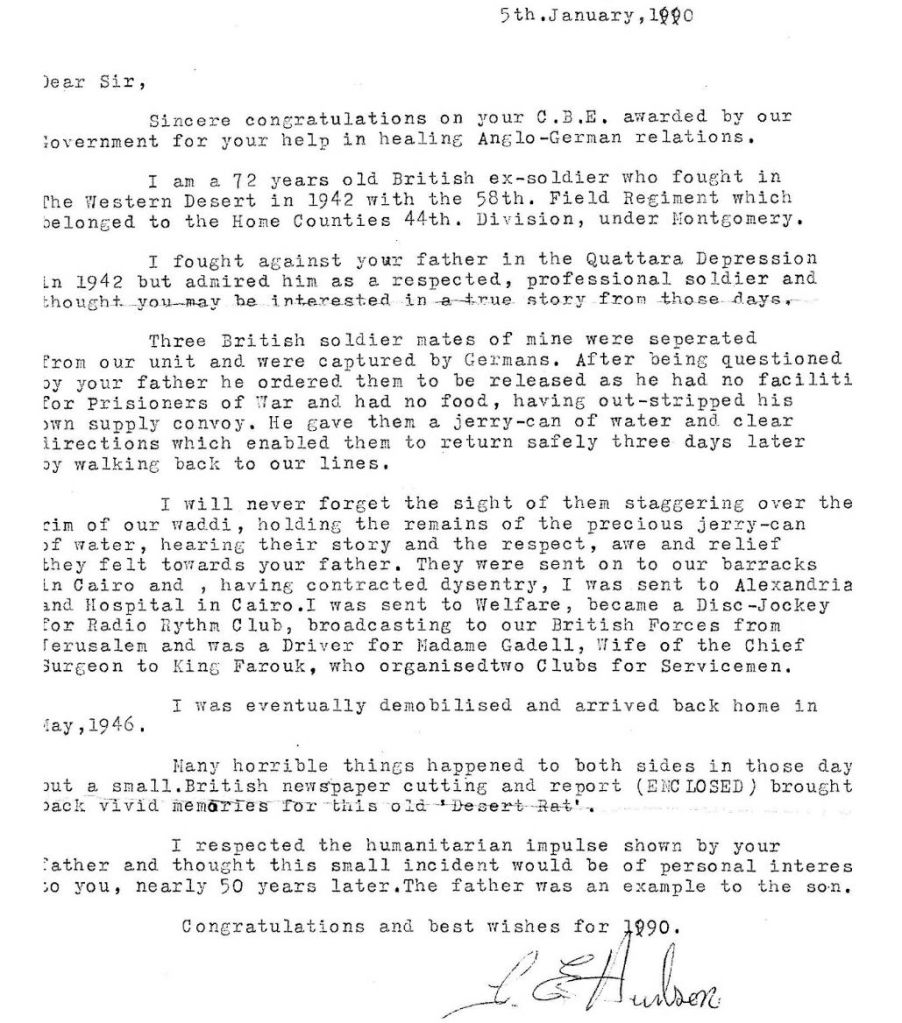

Well me dad were one of the Desert Rats actually. He was a bricklayer by trade, I were born in ’39, I remember seeing him when he come back, I was about six or seven and I didn’t really know him. There were three of us, me, me sister, she were born 18 month before me, so she were born in ’37, and me brother Graham were born after the war like in 1947.

He did his face training at New Stubbin, and then he wanted to come with us and he was shaft man with us at the Mines Drainage Unit up to them finishing.

Terry showed me a letter written to his father by Manfred Rommel, (1928-2013) the only son of the famous German WW2 Field Marshall Irwin Rommel, thanking him for publicly defending his father’s reputation.

Apparently following some criticism of Rommel in the UK press in the 1960s, Terry’s father wrote to Manfred Rommell to say that when members of his platoon were captured by German forces in the North African desert in WW2, after questioning them Rommel told his men to give them water supplies and point them in the direction of the allied lines.

They returned safely and Terry’s father was making the point that Rommel’s behaviour was not that of an archetypal Nazi.

– So where did you go to school?

Round the corner here, there’s a school there, Ashford Road School and I went from there to the Secondary Modern School at Rawmarsh High School. I used to walk up there with the colliers that worked at New Stubbin, up railway line to school and I thought “I’d give my right arm to go to pit with you rather than go to school”. I hated school, I detested school. School weren’t so bad, it were the people that taught you. They were horrible people and I blame it on the war actually.

It must have been terrible for them having a load of kids to put up with, it was terrible they used to bash you about. Think nowt about giving you a belt round earhole for nowt. I left school, actually when I were leaving I took to learning and I used to go back to night school ‘cos I like engineering and that you know.

Terry’s point was that as the able-bodied men were called up for the war service, the quality of those left to teach suffered. He quoted numerous situations where not only were children ‘knocked about’ as a matter of routine, but also that some teachers seemed to enjoy it.

Even when I was a kid at School, I allus were after money, I weren’t happy unless I’d got money, I used to work on the pig farm just round the corner where Ronalds the scrap merchant is now.

Owen Rose ran the farm and was also a working miner, at Aldwarke I think, his son Carl is still about, I saw him recently. He never paid me owt’ but he were good to me. He gave me a little pig and said “Here fatten that up” and I did and I sold it, killed it off and bought another four. I should have been a pig farmer by rights like. But while I was working there he used to work at pit.

An older miner working at New Stubbin Colliery called Donald Price also worked at the pig farm and used to give Terry a lift there. One day when he didn’t turn up for work with the pigs there was a lot of whispered conversations that Terry wasn’t party to, and didn’t understand. He found out much later that Donald had been caught on the underground haulage rope at New Stubbin and dragged into the engine and killed.

Starting at New Stubbin Colliery

New Stubbin (to distinguish it from the older “Low Stubbin”, to the north) was sunk during WW1 by Earl Fitzwilliam’s Collieries on land to the west of Rawmarsh. The Barnsley Bed in the area was worked out, so the shafts were sunk to the Parkgate and deeper seams; the pit closed in 1978.

When I left school at fifteen I wanted to be a motor mechanic and I got this job at a firm at Sheffield as a mechanic but you couldn’t get up to Sheffield from here in them days so me mum just let me please me self. My dad was bus driving at the time and all my mates had gone to the pit and I used to see them when they come home, they used to be laughing and joking so I thought I’d go and get a job and that’s how I finished up. I went on Monday and started on Tuesday and they sent me straight back to school on the standard NCB training course.

It didn’t matter how good you was or how bad you was, everybody who started went to Rotherham Technical College, like it or lump it, and when I started there seemed to be hundreds of kids and College were full.

I’ve never forgot what the lecturer said “If you’re clever go to that end of the class and if you’re a dumpling go to that end of the class”. I looked at my mate and he said “Come on were dumplings then, if we go to the dumplings end we shall be all reight”.

So that’s what we did and funny thing about it was you were there for 16 weeks or 4 months, summat like that, it seemed forever. The only thing I got out or enjoyed about it was they used to tek us down’t pit, I thought that were great. You had three days at Tech and then two days at Manvers or vice versa.

– So presumably you were taught basic pit operations, safety lamps, coal cutters etc?

Then down the pit. The pit training it’s same with owt else it’s like being in the RAF or the Army ‘cos they are dead strict on training aren’t they, trained up to the hilt. I know there were some nutters amongst them but they’re trained up to the hilt and it were same int mining, you were somebody’s trainee when you went to the pit and you never left his side.

If I were your trainee you would stop with me for another six months or whatever, and I wouldn’t leave your side. And then after Training Officer had talked to whoever trained you, he say’s right you can go now to the pit bottom, get your job and you worked with gangs of men, with teams like.

After training Terry started work at New Stubbin as a “clamping lad” working on the main haulage level. His job was to attach full tubs of coal that arrived from each working district onto the continuous rope haulage. This was done by connecting a chain with a hook at one end onto the tub and with a special clip to clamp onto the rope on the other.

There was a limit of ten loaded tubs to be connected at any one point and thirty empties, but Terry and his mates took great pleasure in deliberately exceeding these limits and telling the Training Officer about this to wind him up.

There was always a coat hanging up near where Terry worked and whilst no one said anything about it, Terry found out eventually that it belonged to Donald Price who had been killed when he got caught by the haulage rope and dragged into the engine. This was the man that Terry had worked with at the Pig Farm.

At Stubbin, and I didn’t find out for years after until, I worked on’t main level knocking tubs off what they call on’t rope, and there were a coat hung up, nobody ever took it, and this coat it were there all the time, nobody ever shifted it and for another twenty year I never knew.

It were Ernie Gillespie that worked at Stubbin who came to me and said “This coat you know it were on’t main level, it were Donald’s, and nobody ever shifted it, it were there for years”. So all these years that coat was Donald’s who used to pick me up, small world int it.

And then his brother, Donald’s brother, Bob Price. Robert Price, he used to call him Tarzan because he was just like Tarzan and he were built like it, but he weren’t very big. And I said to him, I sez “Did your brother get killed at Stubbin? “Aye” he ses “He got fast on’t rope” and I’ve been fast in the same place!

I was working on the Main Haulage Level at New Stubbin when the sleeve of my battledress jacket (it was my dad’s old one) got fast in the rope chain and it was dragging me towards the start pulley, I managed to rip the sleeve off to get out of the coat and get free – this is how Donald Price got killed. or I’d have gon’t same way.

I was on the haulage then for a couple of years and I’d had enough then. I said I’ve had enough of this. I had problems at home and thought I would go and join the British army.

I was seventeen and four months and not old enough, they wouldn’t take me, as you had to be at least seventeen and a half. And when I got back to the pit Training Officer said “You’ve been to join the army haven’t you?” I said “Yes, I’m going with me mates, I’m not sticking here it’s too much of a drag like”. And anyway I sez “I can’t see any prospects”. He sez ”when you’re 18 stop with us you can go and do your face training.” I thought that’s just what I want ‘cos I were on good money then.

Training

When I was 18 in 1957 the Training Officer sent for me he sez “You’re going training next week.” Lovely, straight off, I were in. And then I were ont top money, that’s what I wanted so I stuck it out like. The coal face was undercut by machine, then fired. They had a side that used to do what they called “hand gots”, tub it, when the seams were about 6ft in Park Gate, I used to enjoy it to be honest I don’t know why ‘cos it were a terrible job.

And then after a few years the novelty wears off, you know what I mean, and then when I was 22 I thought I’d go lorry driving. I went driving lorries and machines.

Terry starts driving

Well I’d seen Black’s flying about with the coal lorries and I knew where the garage were and I thought well I’ll go ask for a job.

Anyway I went to Black’s. Anyway I sez “Any vacancies?” he sez “What you drove?” I sez “At the moment I’m working at Hoober drift and I’m an unpaid driver and they only send me to the power station with it, bloody old Dodge they’ve got. “When can you start?” I sez “I can start int morning” he sez “ That’s good” I thought “I’ve got a job here” and he said “Can you come int morning?” I said “Yes”.

Anyway, I went next morning and they started at 6, he sez “We ant got a lorry for you”. He sez “We’ve got one there, but it’s no guts in it”. They were A.E.C’s. I sez “Well is it runnable?” He sez “Yes, but none of the drivers will drive it.” I sez “I’m sat here let me see if I can tek it.”

“Well” he said “There’s a load wants picking up at – I think it were Linby, one of the Nottingham pits? He sez “You could go there, but I’ve warned you about the lorry. “Anyway, bloody hell it were right an’all, couldn’t get out of first gear and I finished up, I got lost.

I’ve never forgot about it ‘cos I got lost in Mansfield, and I went down right through the middle of Mansfield when it were market day and I were reight int middle of the market. Anyway I got me load on and I think it were 12 o’clock at night when I got back and he just laughed at it like and just said “I did warn you.” I sez “It’s knackered.” He sez “I know, but you had to prove it to me didn’t you”.

In Sheffield. I were on’t coal lorries at first, running to the pits, carting scrap from Scotland and fetching scrap from up there. That’s a novelty to start with, then you get fed up with bed and breakfast in a stinking bed where someone else has been in, you know what I mean, so I went on’t coal lorries. That were good money, that.

– When you say coal lorries, is this coal lorries delivering house coal from the pit or from pit to power station?

Power station. I did ‘em both, bagged coal to start with then I went to the pool for Black’s in Sheffield, money were good. Basically were £15 but you could make another £10 or so if you went flying round like a maniac. I stuck that for, I don’t know, and then I thought “I’m going to finish up int churchyard here if I don’t like what I’m doing.” I were courting at the time and so I had to move from lorry driving to try and make some money so that’s when I started moving from one place to another.

– So when you finished lorry driving what did you do?

I went on’t machines working for Rails, company based at York, but with a local depot at Brinsworth. They weren’t JCB’s they were Drotts, little ‘dozers, what they called International Drotts. Most of the work was on building sites, if you could handle a machine you could get a job anywhere. I’d already been on’t farms and jumped on’t tractors and stuff when I shouldn’t have been like, so it comes.

Terry wasn’t impressed with Rails, particularly after he was told there was no wages envelope for him just before one Christmas break. Terry stood his ground and payment was eventually forthcoming.

Cementation

Where did I go from there? Oh I think I got a phone call from Cementation, they asked me if I was interested in a job there. I thought “Yes, that is good money that.” They were just throwing money at us,

Mr Chester was the agent for Cementation, responsible for hiring and firing. Whilst working for Cementation, Chester had discussed the possibility of work in some of the Collieries in India – Terry wasn’t keen as he had heard that, unlike UK collieries which closed for the day when a man was killed, those in India did not and this seemed unacceptably disrespectful.

You must have been doing quite a lot of development at that stage?

I went to Shirebrook, I worked at Shirebrook, they sent me there with some of me mates – small world. I worked at Shirebrook and I left in, I don’t know when.

“There’s a job here and I’ve got to tek me hat off to all these men here it’s a fantastic job what they did.” To deepen the main shaft, they went under the main shaft and deepened it. He were really shooting these men off like and he sez “Where do you work?” and I sez “I’m not what you’re on about”.

Money were fantastic, but it were a dangerous job. Well if you’ve ever done shaft sinking it’s very, very dangerous that job. Well, it’s worse than being a collier, because when you’re a collier you can timber up and make yourself safe, you can’t timber the shaft up. That doesn’t work out on that one.

Shirebrook were already sunk, they went underneath the main shaft, deepened that, I think it took it down to the Main Hard. Well I weren’t on it long, 12 month if that, and then I went to Thyssens around 1966.

After Shirebrook, Cementation wanted Terry to move to Kellingley for their contract there, but he was also approached by Thyssens, Cementation’s main competitor who had a contract at Kilnhurst, a mile or so down the road from his home – and naturally Terry opted for this.

They were putting junctions down there, well I’d already done that at Stubbin development And when that were done they told me I’d got to go to Kellingley. I said “I’m not going to accept that, I’m not travelling there every day.” That’s a no go that, so here today, gone tomorrow, I’m not bothering with you, stop or go, and I went to work at Hoober Drift.

Hoober Drift

Hoober Drift was a private mine, owned by Bennett and Hallamshire and Northern Strip Mining that worked what remained of the shallow seams in between New Stubbin and Westfield, within walking distance of Terry’s home.

– So was that before mines drainage Terry?

Yes. I was a face worker there, and I think this guy tried to kill me to be honest, while I was there. There were problems with the workmen and there were problems with the Management but it were nowt to do with me really ‘cos I were a new guy there, so I had no grievance with nobody. But there were bad times.

There were things being done that shouldn’t have been done where they’d had a fall and it had cut ventilation off. You only get so long if ventilation stops, you have to open it and if you don’t open it up Inspectors will shut the pit.

They’d had this fall, and a kid called Ken Stanley, he were a mate of mine and he worked there. He said “There’s been this fall, Manager sez will you come with me and try and get this road through wi’ me tonight?” I said “Yes”. So I went down and we got this road through, I think it was New Year’s Eve when we did it, got this road through. And the Manager came down, Knowles I think they called him, and he said “Have you got through?” and I said “Yes, ventilation’s pulling through, I could feel it pulling through” I sez, so we’re OK, just got to rig it up now.”

And he was over t’moon was Manager and he sez “Here, have a drink of this”. He poured two cups, I thought it were cold tea, it weren’t, it were bloody whisky! New Year’s Eve, I drunk it straight down, and thought – bloody hell, it’s whisky. And Ken he sez “It’s whisky that, I feel as pissed as a newt” and we were, he got us pissed just like that.

Anyway that were for Knowlesy, and then I were in’t coal there and conditions were very bad. They skimped on supports, and if you’re mining near the surface it’s dangerous. What they’d done, they hadn’t timbered it up properly, they hadn’t maintained it properly, the seam were what they called Kents Thick, and this has got a muck band about a foot, 2ft 6” of coal 2ft 6” of core which used to cut it with the Dosco cutter, blow it, fill it, pack muck inside and then float bottoms and you worked to what they called “stalls” they call it.

What they’d done is they’d worked their way out, but they’d not made any manholes, there weren’t no manholes anywhere, plus weight were on and it had set off about 6ft and it were coming down, it were slowly settling down and it were dangerous.

Anyway I was working with this guy called Nixon, they were all frightened of him he were a tall, ugly guy, scruffy, stunk, no better name for it, and I’d been wi’ him only first day when I went with him. Anyway what they used to do was to fill 6 or 7 tubs and then fetch them to the main drift, fetch em out, and he said to me “Go to the end of the level, put bar up” which was an old piece of railway track (called a Warwick) to stop these so that when they were coming down they would stop, anyway when I gets there it weren’t there, and these tubs were on their way before I got there, so they were like chasing me on’t level and there were no way to get out of the way.

– No manhole?

So I didn’t have chance to look for it ‘cos it weren’t there. If it had been there I’d have had it up like lightening and stopped them but I couldn’t. Anyway I finished up, they’d cocked me up and I started to hold em back.

I turned me back on em, and I’m pushing and pushing and if you ever lift a tub up it allus lifts up, there’s like a play between the wheels and the tub, I knew there were 7 and I counted 6 and I couldn’t hold no more and I just managed to lift it up and drop it over, over the rail so it stopped them running o’er me.

I sat down and wept and afternoon shift were coming on and they said to me “What you done/” and I sez “These cocked me up and there’s no derrick here”. So they sez “What you going to do?” I sez “I lifted first tub off half” and afternoon shift couldn’t lift this tub back on.

What I’d lifted off they couldn’t lift it back on. “How’s tha managed to lift this off?” Well when you’re scared and you think you’re doing to die. You can lift a few tons! Anyway I didn’t think no more about it like, and I thought about it since that, that bastard tried to kill me because he knew that that the Warwick weren’t there, and he sent ‘em and because they’d had confrontation with the management they wanted somebody killed to cause a bigger confrontation to get pit shut …

– So you weren’t there that long then?

Oh, I got caught in the middle of that, yes. And when I first started he were allus, I knew there were trouble but I didn’t think it were that bad. I didn’t think I were going to be in the middle of that, so in the end I just left.

– So that didn’t last long, so you were off to the mines drainage unit?

No, I went up Readymix from there, went on’t Readymix. Pioneer Concrete came to Sheffield and they wanted some drivers, drivers who were interested in buying their own lorry and that’s where I went with the intentions of buying me own lorry.

And I would have done I think, but what happened were, Ray one of the drivers, he were a nice type kid an all, he stopped for a haircut and he were outside barber’s for 20 minutes when he come back he’s got this bloody Australian who were full of his sen, it was an Australian firm. Well he were a horrible person, a proper arrogant bastard, anyway he sacked Ray for being in’t barber’s like.

I said “He’s only been for a haircut”. He said “Who told him to go for a haircut?”. I said “It were only 20 minutes.”. “Ah but he shouldn’t have gone.” Yes, I thought You can shove your job up your arse. They just tret him as though he were muck and I thought I’m going to be next. There were about 6 of us and I thought I don’t want to be working for an Australian who walks about, doesn’t speak to you when he passes you anyway. Do you know what I mean?

And then, you’ve never worked on the Readymix have you? That’s another education, the jobs we had. It’s OK as a novelty. All of a sudden you’re sick of the sight of concrete, everything that come out of the lorry is concrete, concrete, concrete.

Well it’s a good job, you had a chance to check it out before you did anything. Well once you’d have signed up for the lorry, you know you’d have been stuck wouldn’t you? I forget where I went to from there, oh I think I went on to the machines ‘cos I liked machines. I didn’t bother, I’m not one of those who, I can’t do this and I can do that, you can’t take me hands.

Then it’d got to about 1968, I think, and that’s when I went to Mines Drainage. I had one or two mates who worked there and I went for a job and I saw the Engineer, George Law. He were the Engineer was George, an electrician by trade. Before I started at Mines Drainage there was a guy there, Manager, they called him Major Saul? He still carried on with the Major, he was the Manager of the Mines Drainage Unit.

– Did Bob Ditchfield interview you?

No, I saw George Law, and I came out and Bill Ridgeway was there. He used to be top labourer. And I said “I’ve been for a job Bill” he sez “Ah, who have you seen?” I said “George”. He said “He can’t set you on, you’ve got to see the Manager”. I said “He’s not in, t’Manager”. Anyway, I went home and he sent somebody up to our house – we hadn’t got a phone in them days – would I go back down and see Bob Ditchfield, so I went to Westfield House and he asked me where I’d been working and what I had done.

Well he said “Why did you leave Stubbin?” I told him “I didn’t want to be there forty year and then and have the same job”. He said “Well you’ll have to go to Manvers and be trained.” I said “Well I don’t mind.”

Anyway I were with what they called the “adults” and there were about five or six of us and we used to go down the Training Gallery and I’m talking and telling the instructor where I’d been and what I’d done and he were sat there with his gob open because he’d never done any of this.

He sez “Well, I’ve been talking to the Manager Terry, you’re going back to the Mines Drainage.” I sez “I’m here for 4 weeks.” He sez “No, you’re not, you’re going back tomorrow”. He said “I’ve been talking to the Manager and said he’s been learning about all this pillar and stall at the Hoober Drift, and I’ve never done it.” He sez “You’ve got to have done that for the Under-Manager’s ticket, so you’ll be coming back as an Official with the Deputies like.” And I were, I went straight there.

I come back to Mines Drainage and money were absolutely shocking, £12. And Wendy’s saying “This money’s not much good, I don’t know how we’re going to manage”. And I thought “I’m going back to Cementation”. I was going to go back ‘cos they were getting good money and see if they’d have given me a job at Cementation again.

Mr Chester said when I had left before “Any time you want a job come back.” And they were getting good money, so I was going to go there. I must have told somebody and he must have told the manager and he said “You must go on a Deputy’s course you can double your money.” I said “There’s nowt wrong with the bloody job I can’t live on the wage, it’s as simple as that.” And he sent me on the Deputy’s Course so I were back at school for another 6 months at Mexborough Tech.

– I understand what a Deputy does but what training is needed?

Well to qualify for a Deputy you’ve got to have done your face training. And then you’ve got 6 month at Technical College and you sit your exams from Mining Science to Mining Mechanical, anyway you’ve to sit your exams and pass your exams, and I’d done that, passed that and I finished up Grade 1 Deputy.

– So what did you do as a Deputy for Mines Drainage? I understand if you were at a normal pit you’d do a set piece every day and know what your routine’s like.

Completely different, nothing whatsoever. We used to start, I think it was half seven, everybody reported in up here at Westfield House and we had a fleet of Landrovers to take us to the pits. There were about seven or eight Landrovers and they were all in teams, like.

– How many men worked for mines drainage at that time?

You didn’t used to have so many, but then pits started to close so they built up. Bob Ditchfield in his wisdom built it up to make teams up to go and close these pits.

It were a crafty move because we had Landrovers, there were no name on’t side as nobody knew who we were, and the idea were that sometimes, I mean the Coal Board didn’t allus do everything as they should do. You know, if they were flooded out the all over farmer’s field, and we used to go and they used to say it’s bloody Coal Board ‘cos they didn’t know who we were ‘cos we were all in scruffy and all in Landrovers like, so we just used to disappear and they didn’t know where we were from; they couldn’t ring and complain.

– So how was your work allocated, did you have a roster board and knew what you were doing?

Well it just depends what you were doing. I were allus ont’ front line like, you know what I mean? When I say ont’ front line int’ pit, if there wa some shafts that was collapsing or summat, they were liable to get squashed or summat like that then I used to go and look at jobs with Bob Ditchfield, and he used to say, I think there were six of us Deputies at that time and it went up to eight, he used to say “It’s horses for courses”. But we were all ont’ same money.

NCB Mines Drainage Unit – How it worked

At this point, it’s worth explaining how the Mines Drainage Unit functioned. It was unique and without parallel in the UK. This description is based on Terry’s and others’ descriptions, and far from complete.

The NCB Mines Drainage Unit was the successor of the South Yorkshire Mines Drainage Committee (SYMDC). The SYMDC was established in 1929, taking over from the South Yorkshire Pumping Association, to manage the pumping stations that had been established to remove water from the worked out areas of the Barnsley Bed to prevent its descent to the deeper workings of active collieries.

Originally called the ‘Fitzwilliam’ scheme, as most stations had originally been commissioned to protect Earl Fitzwilliam’s collieries between Rotherham and Elsecar in the previous century.

Some details of their operation in the period before WW2 are given in my “SYMDC in 1939” article (published in British Mining, No.100, Memoirs 2015, Northern Mine Research Society), but for the purpose of this account the main activities of SYMDC before the NCB took over in 1947 can be summarised as:

- Ensuring the economic and ongoing operation of the pumping stations;

- Ensuring the drainage levels and watercourses into which the pumping stations and working collieries discharged the water raised were functioning as required;

- Undertaking specific construction projects to support the above.

As a result of requests from working collieries that needed dedicated water drainage expertise, a number of additional pumping stations came within SYMDC’s remit before nationalisation in 1947.

SYMDC’s operating costs were originally funded by the colliery companies whose pits the scheme protected, charged on a proportional basis determined by the volumes of water raised. This arrangement depended on detailed records of operational and project expenditure being made, and because many of these are available from archival sources, a good understanding of SYMDC’s work is possible.

The NCB Mines Drainage Unit (MDU) is understood to have been established at nationalisation in 1947 to takeover SYMDC’s work. It would appear that between 1947 and 1988 when the unit’s work was outsourced to external contractors, its main activities were:

- Continuing the work of SYMDC to ensure that pumping stations and drainage levels were operating effectively. There appears to have been a regular schedule of visits and inspections for all sites.

- Extending this remit to include selected mines drainage stations not included in SYMDC’s original scope.

- Providing development teams to those NCB South Yorkshire Pits that requested them, particularly where shaft work was required. “Development” is a term for the preparatory work needed to enable working coalfaces to continue progressing without interruption. It entails driving roadways, building junctions and on occasions shaft and water management work. Some pits had “in house” development teams, some were sourced from organisations such as Cementation and Thyssens and others (at least in Yorkshire) were manned by MDU Staff. The choice between internal or external teams is presumed to have been made by the colliery manager – who was measured on the cost of coal extracted.

- The MDU’s services were often required in the event of a major accident or disaster in support of the Mines Rescue Teams, the Lofthouse inundation being a notable example.

- The unit was also called in to deal with those water management issues beyond the capability of the pit’s own staff

- Responsibility for licensing and oversight of small mines (those operating outside the NCB organisation and normally with less than a certain number of men) was transferred to a dedicated Small Mines Unit

It was clear to me from Terry’s descriptions of his relationships with “management” in general, that he was not the most compliant of subordinates and did not suffer fools gladly. It was also clear from his interview that he held Bob Ditchfield, the MDU Manager, in extremely high regard.

Terry at Kilnhurst

Terry first worked at Kilnhurst for Thyssens on new developments before he joined the MDU. He came back to Kilnhurst when he was working for the Mines Drainage, spending seven years there in all.

The numerous local pits in this part of South Yorkshire were obvious candidates to call on the services of MDU. Terry must have been an obvious candidate for work at Kilnhurst as he was fully trained, and had already worked there.

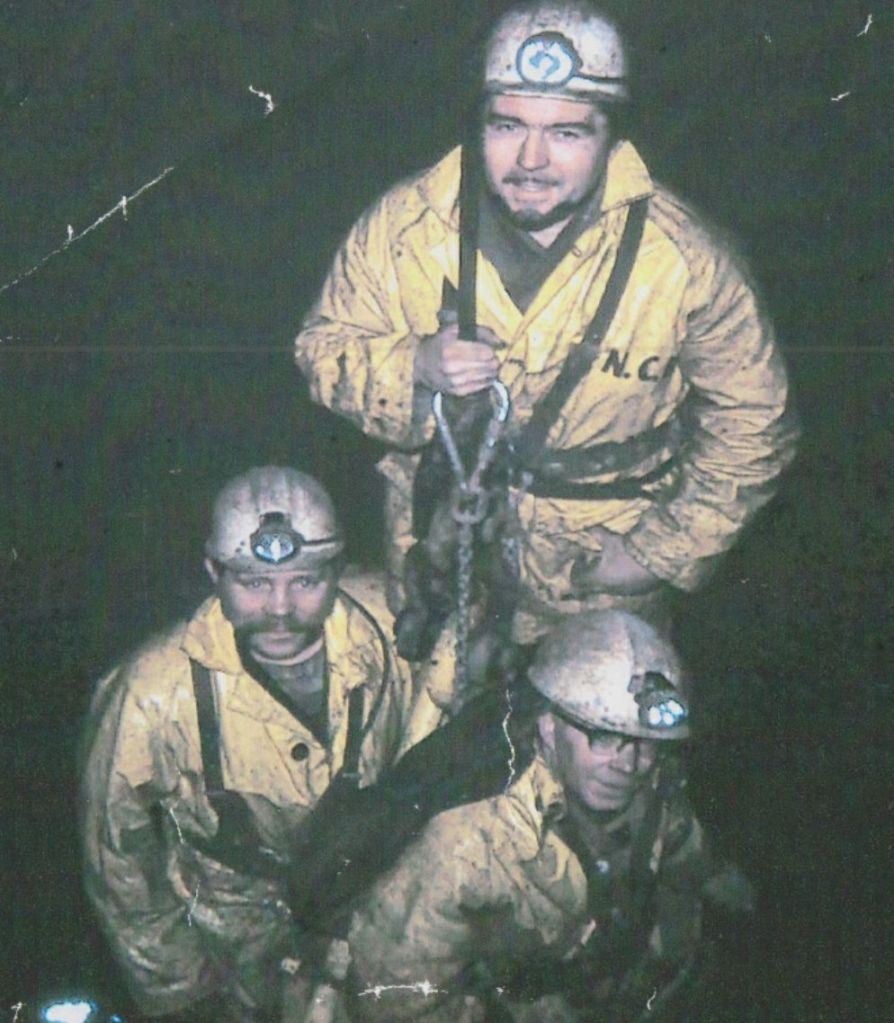

He told me that whilst he was working there in the 1970s, there were 2 four-men teams working there:

– Alf Hutchinson, Jack Ridgeway, Colin Mitchell and Bill Jeffries worked on the afternoon shift whilst Terry, Jack Cartwright, Frank Underhay, Percy Damms and Jim Evans worked the day shift.

Much of the MDU team’s work was on development, but Kilnhurst had a particular problem with damage to the lining of number 2 shaft that Terry and his colleagues were tasked with fixing. I found Terry’s account of this most insightful and it seems to have developed thus:

Number 2 shaft, the upcast had been deepened before 1931 to the Silkstone seam at 653 yards deep and widened in the process, this narrowing (Terry and colleagues called it a “bottle shaft”) had the effect of creating a chimney like effect that increased the normal upcast air velocity.

Number 2 shaft had been troubled for some time by weakening and collapses of the shaft lining, and whilst it had not resulted in any injuries, it was an obvious concern, and indicator that all was not well.

Examination of the area of the collapses (in hoppits, the normal way of working in shafts) indicated the cement lining between the brickwork and shaft walls had been washed out by persistent water flows. It was agreed that the shaft would be relined and Terry and colleagues undertook this work down as far as the Haigh Moor inset. They used rings (secured to the shaft sides) and boards (laid across them to work from) to do this. Working in an upcast shaft was particularly tiring, the constant air flow leaving the men with permanently bloodshot eyes.

This relining however had not solved the problem, and given that the Lofthouse inundation was on people’s minds, Bob Ditchfield wanted to understand more about where the water was coming from. He set Terry and his colleagues to drill the walls in No.3 pumping shaft.

Working from a temporary winder and hoppit (No.3 shaft was the old pumping shaft, so had no cages), and using compressed air drills, Terry’s team drove a series of boreholes into the shaft walls at regular intervals. It quickly became clear from the pressure of water in some places that there was a build-up of water, and that its source was most likely to be the abandoned working of the shallow Swinton Pottery (Colliery).

I said to Jack and Frank, 2 lads, that – “There’s summat here in’t there”. That watter is coming here full bore, and we can’t stop it. This was end of shift.

They sez “We’re going to have to go back”, I sez “No, we’re not stopping, they can shove it up their arse, they weren’t paid face rate, they can arsehole.” Anyway they went up, I sent ‘em back to the yard like, and I stopped there. I sez “They weren’t paid face rate and guess what, all the men are going home from the pit an’ all because we’ve flooded main shaft now”.

What we’d done, we’d hit this water and it were coming in, and it were coming down where we were, and it were flooding old water lodge, going on a level and down the main shaft. It were an excuse not to go have to work and get paid like. Anyway, there were bloody hell on then.

– When you were in the water shaft Terry was it still used for pumping?

It had been used for pumping, but it had been left with what they call a water lodge in it, they’d just abandoned it. Left it see.

Anyway Dennis Carr came from Manvers, and he said “Why haven’t you informed us of what you were doing?” I sez “Inform you, I’ve been here 7 year.” He sez “You’ve not informed us that you were boring.” I sez “Who are you anyway?” He sez “I’m the Area Shaft Engineer”. I looked at him, “Shaft Engineer, if you’re the Area Shaft Engineer, I’ve been here 7 year and never even seen you”.

Anyway I later found out that he’d put that title on his sen. They’d sent him like, to see what were up, and he’d decided to give me a bollocking, but he’d got one back! What had happened were they’d abandoned it and never bothered putting another pump in.

They did put another pump in on a level but what happened were they used to pump this water up on its way to the surface, it didn’t solve the problem. If they did owt they did it for a reason, if olden hands do owt, if they’d done things they’d done it for a reason. And what happened were, I couldn’t stop it, I could slow it down but I couldn’t stop it.

It were going down the main shaft like, so you’re going to get bloody wet. There were chuffing hell on, so Manager didn’t say anything, Jack Benham was the Manager at the time but he didn’t send for me, he didn’t say a thing to me at the time.

Anyway, I went down No. 2, walked through into this inset. There used to be a puddle just like this in this inset, I’d examined this inset for the last 7 year and this puddle were here, didn’t get no more didn’t get no less. Anyway, this puddle it went down, and I walked on the roadway and it were like, I’ve never seen nowt like it. If you’ve been to Blackpool and the tides in and it’s bashing up against thing, it were just like that, ‘puth puth’. And I thought “Christ Almighty, what’s up?” I didn’t know what were happening, you know what I mean.

I thought “There’s summat, but I don’t know what it is”. So I made a beeline for the Manager, they keep out of the way, but if there are any problems they don’t come looking but I thought “He’s got to have this, he’s got to come and have a look at this.”

I sez “I don’t know what’s happening, I need some help”. Well, he come down and have a look, he sez “Do you know what it is Terry?” I sez, “No, I don’t”. He sez “What do you think it it?” I sez “Well they’ve abandoned the old pump lodge, they’ve not bothered pumping any water”. This was before mine or the Manager’s time. I sez “I’ve bored, I’ve tapped this water and I’ve started to lower it so I’ve short circuited between that shaft and the upcast shaft” and he sez “Yes, that’s what’s happened.”

By this time Ditchfield were there, and he sez “What do you think we should do Terry?” I sez “What do you think I should do?” He sez “I’ll tell you what we’re going to do, we’re going to let it keep coming.” I sez “What about that bastard from Manvers?” He sez “Tek no notice of him, I’ll sort him out.”

Anyway they let it go, when it had run off, it took it about 3 week or a month to run off, it were a long time, and what it had done, because they’d stopped pumping and because everything had ockered up, where water used to come into this pit bottom, it were complete pit bottom and when it had run down and it were 20ft high and it were as big as any coal mine, it was complete pit bottom and we followed it as far as we could.

Well we didn’t go to the end of it ‘cos we knew where it was, and it were too dangerous for it, and it went from Kilnhurst to Swinton. What it actually were and what were causing this No. 2 shaft to collapse, the water course falls from Kilnhurst to Swinton and it were shoving on that shaft all the time.

Terry seems to have had an affinity to water management issues, he told me of a series of violent summer thunderstorms whilst he was working at Kilnhurst that resulted in water running off the tip and disappearing near to the shaft. Seeing this, he purloined a JCB and started to dig a trench to divert the water, in the process of doing this he was near the main fan and managed to cut through a 30K volt power cable taking current from the colliery to British Railways. This shut down the railways in the area but at the subsequent investigation, Terry was cleared of any fault.

Bob Ditchfield‘s view, according to Terry, was that the quantity of water backed up would have made the Lofthouse disaster look like a swimming pool!

An accident at Kilnhurst

When Terry and I were making corrections to this account, I saw a letter of commendation from the NCB Management and I asked Terry what it was for. This is what seemed to have happened on the 31st of July 1975.

For their efficient operation all pits needed a range of plant and equipment and at this time small tractors and JCBs were commonplace. The yard tractor at Kilnhurst was driven by Cobby who wore an eye patch, and could only see out of one eye. His “mate” who worked with him was David Hart, a lad that Terry describes as “eighteen going on ten”.

Terry recalled threatening to clean David’s teeth with a wire brush as he was sure they had never been cleaned since he lost his milk teeth. I recall a few kids like this from my own youth, often characterised by wild behaviour that was presumed to be the result of erratic or absent parenting. David was free with his insults to all and sundry but no retribution was ever meted out because of Cobby’s fondness for and protection of David – Cobby having a reputation as one of the hardest men in the pit!

David regularly sat on the tractor’s mudguard whilst Cobby was driving but one day the inevitable happened. Terry was working on the shaft top and became aware of the unusual silence pervading the yard, searching around to locate the cause he found David’s inert body beside the tractor, Cobby having reversed over him. Terry gave mouth-to-mouth resuscitation and organised the first aid men with stretchers but it was all in vain.

MDU Regular activities – Footrills and Watercourses

When Terry was working for the MDU he was living close to Westfield House in Rawmarsh which was the HQ. The day-to-day activities of both SYMDC and the NCB’s MDU were based around two main “centres” of operation with a number of sites close together.

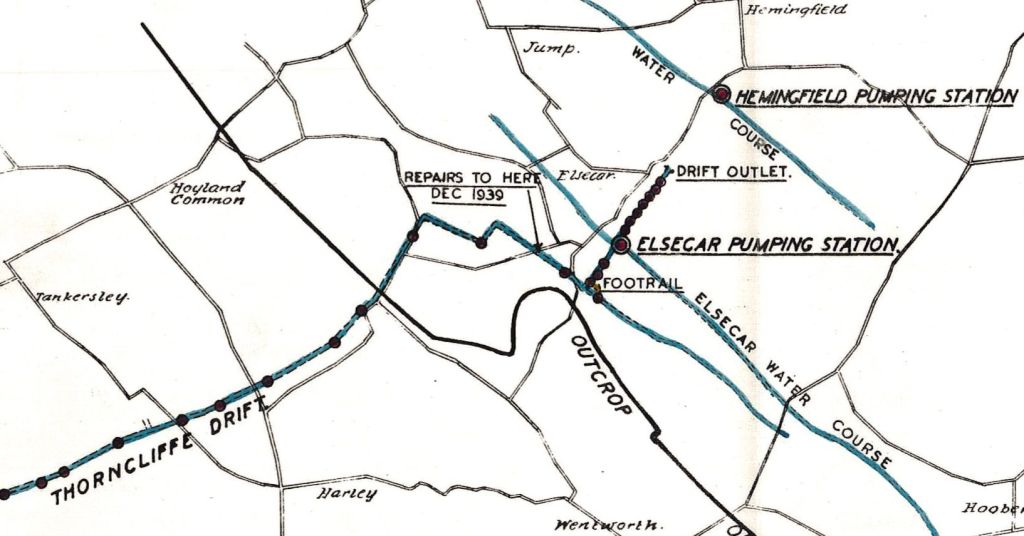

The first was around Westfield and Parkgate, and the other was Elsecar and Hemingfield. There were additional pumping stations that were visited regularly, but I will use Terry’s descriptions of the regular cycle of work at these two centres to help our understanding of MDU operations.

Westfield

Westfield House had been purchased by SYMDC in the 1930s to provide all the facilities needed for a HQ. Less than 100 yards down Westfield Road, on the opposite side was Westfield Pumping Station and Workshops.

Both buildings are still intact, Westfield House is now a care home, and the 1823 Newcomen Engine House and its 1930s concrete headgear still exist as part of the workshop complex, most of which are now used as rental units.

Until 1990 these workshops were used by the MDU and dealt with most of the wide range of mechanical and electrical tasks needed to keep pumping and drainage operations going, much of which included pump refurbishment. The workshops capabilities extended to complete rebuilds of the underground diesel locomotives used at the nearby Wentworth Drift Mine.

Westfield sits above two important lengthy watercourses that run in parallel roughly south-east from the watershed around Wentworth to discharge into the River Rother near Parkgate. The shallower, more westerly “Top Watercourse” discharging directly and the deeper “Bottom (Low Stubbin) Watercourse via the Westfield shaft, both essential parts of the system ensuring that water in the Barnsley Bed goaf did not percolate deeper.

After closure of the pits in the immediate vicinity such as Elsecar Main, Cortonwood, New Stubbin and Kilnhurst, the value of this drainage system diminished, and maintenance was progressively reduced, while pumping ceased at many of the stations.

These watercourses were accessed by “footrills”, the local term for sloping mine entries used instead of shafts for shallower workings. The Top Watercourse was accessed by an entry a few hundred yards west of Westfield, at the end of Occupation Road. The Bottom Watercourse system was accessed via the former also, and then through the cross-measure drifts at New Stubbin pit.

These mine entries also had the advantage of not needing a winding engine, banksman and the associated infrastructure, and so were normally visited by just a pair of MDU men; one a fireman, and the other to do the particular work required.

In addition to looking after any underground pumps and electrical equipment, MDU staff took regular measurements of the water depth at set “V notches”. These simple mechanisms were small weirs cut in a V shape into the beds of the watercourses at strategic points. The depth of the water over the V notch was important and always measured in GPM (gallons per minute). Underground water flows are less variable than those at the surface, so reductions in water levels on the V notches were normally indicative of blockages or diversions upstream, and served as a prompt for further investigations.

The MDU had another quite unusual routine task near to Westfield and this involved taking regular air samples from behind a sealed wall surrounding the long burning underground fire at Upper Haugh.

Before 1990 the MDU’s routine tasks around Westfield included:

- Weekly visits to check the electrical pumps at the bottom of Westfield Shaft

- Weekly visits down the footrill to take air samples

- Weekly checks on water levels across the V notches

It goes without saying that the data collected on each weekly visit was recorded and signed for as a basis for longer term analysis and reporting.

– Terry tell me again about the footrills? Tell me first of all about the one you used to take the ends off the pipes, sample it and send it to Manvers.

Off fire wall? Yes every Friday either I did it or another Deputy or official had to do it. And you allus had a general underground worker or shaft man with me. They used to walk down the footrill here.

– So the footrill down the bottom of Occupation Road?

Yes I used to go down there and walk from there either under Westfield House ‘cos pump house is slap bang under that big house. Yes and I used to walk up through Park Gate seam, no, it weren’t Park Gate it were ——-? I don’t know that it were Park Gate, I can’t remember the name of the seam now.

Anyway that’s by the way, but I used to walk from there, and there used to be a footrill gate to what they call the top footrill just before you got to. If you go on the back lane there you’ll see where New Stubbin Pit was. Well just before there on the right hand side, that’s where the top footrill were and that’s where they put fire wall, there. I used to walk that, or somebody did, and sign for it every week.

– So what did you do, go in, take the taps off?

Well they had these bottles, you’ve seen these pump bottles what fit on the pump, they used to pump it into that and mark ‘em off, what date, what time were. Well it has a valve with a tap on it and a pump, right. You put this pump on and it sucks it out, you know what I mean, it seals it as it – you’ve got a cartridge about as big as that and that’s got a sample out of here, and you have to write date, time and – what you did.

– And what did they do with it at Manvers, I mean obviously checked it for chemical contents but why?

Well, it’s carbon monoxide, it’s burning the rubber, it’s burning all the time, it’s never stopped burning. I’ve heard people say that it’ll never burn out, it’ll never stop burning, it’s still burning. How long’s it been going. I’ve read about when it first started, I’ve heard that many tales – –

– How far in were you from the entrance to the walled off area, Terry, was it very far?

Well I don’t really know the district but the fire wall went full length of, more or less, the walkway because there were no timber or owt set up. Well I think it had been mined, but it were like it when I went there I never saw any timber up, there were no timber. Literally walked through the coal seam and that’s why I say I think it were Park Gate ‘cos it were about 6ft thick. It were built in brick and there were one or two different places to tek samples to Manvers.

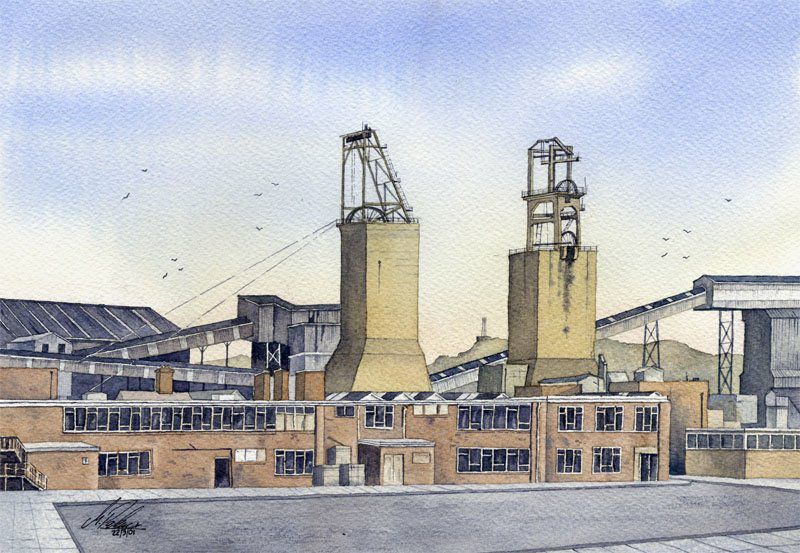

Elsecar and Hemingfield

Elsecar was the other centre of operations for Earl Fitzwilliam’s (EFW) Collieries and, when the Barnsley Bed was worked out and the collieries closed, the pumping stations continued working and were taken over by SYMDC from 1920.

Hemingfield Colliery, less than a mile east of Elsecar was the last of EFW’s local pits (Top Stubbin at Rawmarsh was the other) to raise coal from the Barnsley Seam and after closure in 1920 was converted into a pumping station.

Fitzwilliam’s nearby Elsecar Main Colliery was sunk in 1905 to work the Parkgate Seam underneath the Barnsley bed, and so the Hemingfield workings remained open, drained and partially ventilated until closure of Elsecar Main in 1983.

In Elsecar itself, the MDU pumped from the shaft beside the Newcomen Engine and also needed to maintain the lower end of the Thorncliffe Drift, a lengthy watercourse draining the Elsecar Valley and the area to the west as far as Tankersley.

The Thorncliffe drift was accessed via the footrill driven in the eighteenth century that originally gave access to EFW’s local coal workings. The blocked up entrance of this footrill is still visible just west of the Heritage Centre, and it also gave access to the pumps at the bottom of the Elsecar shaft.

Before 1990 the MDU’s routine tasks around Elsecar included:

- Weekly visits to check the electrical pumps at the bottom of Elsecar and Hemingfield Shafts

- Weekly visits down the footrill to take air samples.

- Weekly checks on water levels across the V notches.

– Talk to me about Hemingfield Terry?

Well it were used as a pump shaft. It had pumps, one as old as Adam that were in it.

– So did you have to go up and check the pumps at Elsecar and at Hemingfield?

We used to do it every Friday, if I didn’t do it somebody else did it, to mek sure it were pumping OK, and that water were kept away from Elsecar.

Every week, it would be half a day getting ready for a start, making sure everything were alright like. Then me and the electrician would go down the main shaft and he’d check what he’d got to check. I’d do the district before he went, mek sure it were safe, mek sure there were no gas and electrician would check that pumps were in order, floats and everything were working. And I went one Saturday morning, sometimes we used to do it on Saturday if you’d been busy you’d do it on Saturday. And I went one Saturday and it were full to the top with water. Had to pump it out, it took us nearly all day to pump it out.

– What did you do, get a submersible pump?

Well I think it had a submersible one in it, put a sub in it, but even though it had this sub, it’s probably still in it. Is the shaft still there? Well, there must have been a sub in so they’d pump out with the submersible but he insisted that it were examined every week.

– Can you tell to me about Thorncliffe Drift, did you go down the footrill at Elsecar?

Yes. It had to be examined every week. What they had is, on the watercourses they used to have what they call a “V” Notch, so like if, where that watercourse goes down there’d be a “V” Notch there. He used to insist, the Manager, he wanted that “V” Notch measurement every week. If it were 3”, 6”, or whatever it were, he knew what were happening in the water course didn’t he?

– “V” Notch is where you have like a mini-waterfall for want of a better description, in the flow?

Yes and if you measure the “V” on it you’ve got a tape measure, see what I mean. If it’s increased, you know what’s happening, and he had these planned all over so he’d know what’s happening.

There was a small Sirocco Fan just by the Newcomen Engine the first time I went.

The lads used to power it up, it was a pusher fan rather than a puller fan, somebody told me, and I think it just cleared the shaft top.

Well I can tell you now, that shaft used to fill up with methane, there’s some deadly gas there. Well it’d be chock-a-block.

Well I used to go down, you know the entrance to the park, just as you go down the dip into Elsecar, there’s an entrance to the park on the left hand side.

The footrill was on the path as you turn right. On the right hand side there’s a car park. And the footrill used to have an iron grate in the ground there and I used to go down there every Friday or somebody else did, and on the right hand side as you went down there was a big “V” notch there, he used to want that measurement.

And then sometimes, not every week, we used to go down there probably once a month, he’d want us to walk through and you came out at the ladder shaft, and that were full of methane.

– Just by the engine. Why was it full of methane Terry?

I don’t know. Well, I’m telling you I don’t know, I do know, usually it was because there’d been no proper ventilation. If it were allowed to ventilate, but if they’ve sealed the shaft top with steel plates or summat like that, some idiot decides to do that, you know what I mean. I can’t understand why they’ve left it all, it doesn’t make sense.

That’s been sealed up when they were shutting everything but they never shut ??? either did they, they never did these shafts like. Why I don’t know, I used to think it was because I think myself I mean our Manager used to say “There’ll be a big bang one day” and that is because they’ve shut all the pumping stations and nobody knows where it’s going.

Well nobody knows what’s going to happen to it. Like I say, I know Fitzwilliam was a clever man and he did a good job engineering wise and everything, you can’t fault him. Now then everybody just abandoned it you don’t know what’s happening.

MDU visits to other pumping stations

– What’s the Pumping Station at Barbot Hall for, it’s quite a new place isn’t it?

Barbot Hall was a borehole. They had a submersible pump in it, it were in the middle of the field, if you get any photos you’ll see like a derrick in the middle of the field.

Well, that had a submersible pump in it we had one or two problems with that bugger actually. What happened were, I weren’t Official on it at the time. They were tekking it out, team of men that were tekking it out, what they’d done, if you’re taking a submersible pump out it’s quite a bit of weight. They had all that gaffered, they had lifting tackle, they used a winch probably like that little winder that’s still in it.

What happened were the cable that came up with it they tek it off at pump and coil it up on the top, what happened there was they didn’t fasten it back, so with it being wet and slippy, it set off, it just coiled up half way down and they couldn’t shift it one way or the other. So they tried to use washing up liquid and all sorts to try and pull it back, how they got it out I don’t know, It weren’t my job, it weren’t my bullock.

– Presumably they put the borehole there because it’s an area they couldn’t drain from other means?

Well, you see if you think what I told you about Kilnhust, that pit were in high production, one of the main shafts kept collapsing and getting buried, burying cages and things like that. Something’s wrong somewhere in’t it. You can’t ignore it, some people do ignore it, they have ignored it, this is what caused the problems. What’s this problem, what can it be? Well it could be water from Barbot, we’ll put a borehole in there, we’ll get borders in, tek a borehole down, we’ll put on full start getting rid of that. I couldn’t tell you the nitty gritty on it ‘cos I don’t know.

According to British Coal’s Silverwood closure report of December 1994 (kindly provided by John Hunter, FoHC’s “guru geologist”):

“There is no historical evidence of any inbye water feeders at Silverwood. Water enters the workings down the shafts and from Barnsley roadways (probably leakage from Car House & / or Rotherham Main. Approx 264 gpm of water is pumped from the pit, nearly half of which is derived from Barnsley seam roadways.

Barbot Hall pumping station (borehole) pumped until May 1988 at an average rate of 125 gpm from the Parkgate/Thorncliffe horizons to reduce the hydrostatic head on a leaking barrier to New Stubbin. After cessation of pumping, the water level rose from ~160mBOD to 60mBOD, but dropped back to 120mBOD in Oct/Nov 1992 and the level remained between 110-120m.”

– Did you have anything to do with Car House, Terry?

Yes, I used to do Car House, that were done every week, I signed for that.

I think it was on a Friday when SCS had taken over, and they did the same things. Could you go underground, there was no winder at Car House was there?

No. There were some subs in though. Did they tek it down the head gear?

But we used to walk into the shaft top and go down some steel stairs.

I think they knocked it down this last year. (2016). My mate bought it, KCM Skips.

John Hunter explains that Car House pumping station was established to prevent water in the Barnsley seam workings from migrating into Silverwood Colliery. Pumping stopped there in 1988, leading to increased leakage into Silverwood. Upon closure of the latter, the water is likely to migrate towards Maltby &/or Rossington (Car House pumping resumed for a while).

At Silverwood there was a general emission of 570 l/s methane from the workings (as detected in the fan drift). During barometric depressions, the make can increase to >1000 l/s. The closure scheme incorporated venting of methane.