Putting a name to a face is one thing, but what about a face to a name?

John Hartop is a name few might instantly recognise, and yet, from 1857 to 1886 at least, one which figured largely in the working lives of hundreds of Earl Fitzwilliam’s colliers and their families around Elsecar and Parkgate. Despite this there appear to be no obviously identified images or published photographs of him, unlike many other prominent figures before and since.

Even when people lived and worked well into the era of photography, it can be a challenge for local or family historians to track down such images. Photographs may survive, unlabelled or unloved; faces unknown, names detached as it were; the context lost, and as friends and family fade away, time dissembles all.

So, where to begin for a name without a face?

Perhaps at the beginning…

A Sheffield Story

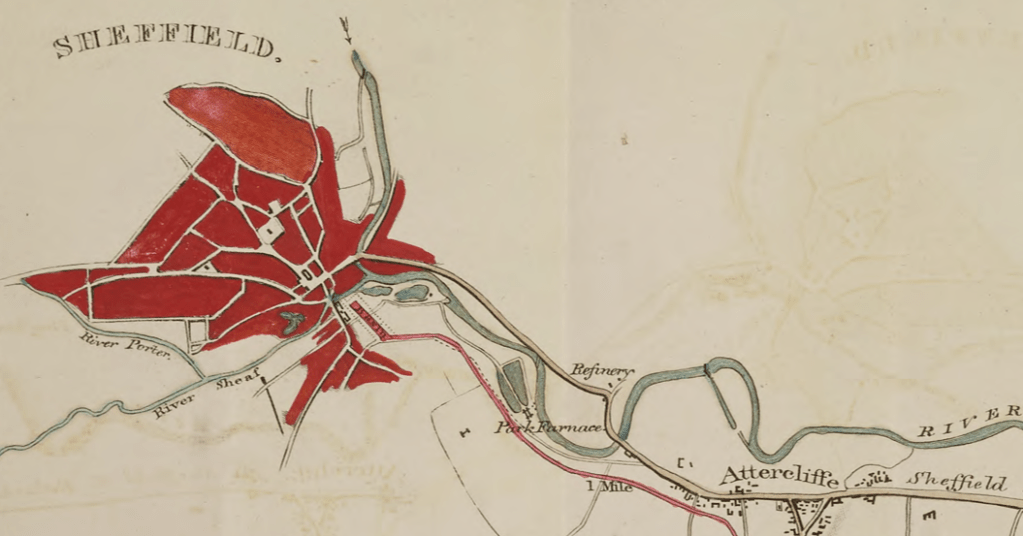

John Hartop’s parents, Henry Hartop (1786-1865) and Anne Sorby (1787-1868), were married by licence at Sheffield Parish Church in 1810. Henry Hartop was an iron founder, and through his parents John Hartop (1745-1788), and Mary (née Binks, 1764-1829), and later his step-father William Littlewood (1765-1812), he was connected to large scale iron and coal businesses.

Early life at Attercliffe

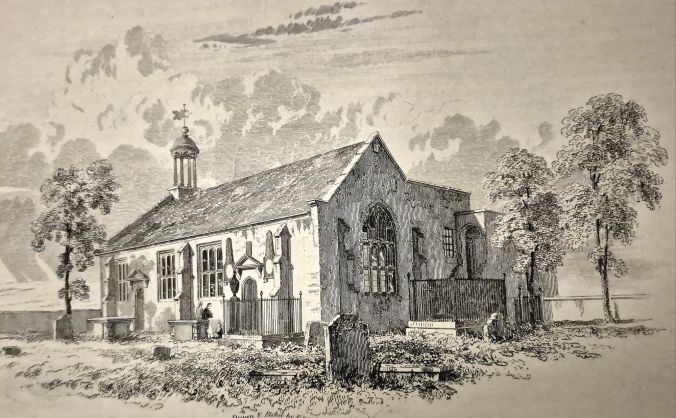

engraved by George Cooke, from Gatty’s Hallamshire, 1869

[plate originally published 1819]. Shows a view of Sheffield by the River Don.

John Hartop was born on 11th December 1815 at Woodbourn (House) in the township of Attercliffe-cum-Darnall in the parish of Sheffield. John was the third of Henry and Anne’s four surviving children, and the only son. The family resided at Woodbourn from 1810 until 1821.

John’s elder sisters were:

- Amelia (1812-1851, married John Francis Sorby in 1837, at Wentworth, was buried at Barnburgh),

- Helen (1814-1901, married Henry Holt in 1847, at Barnburgh),

- and his youngest sibling:

- Ann Elizabeth (1817-1893, married James Hall Nasmyth in 1840, at Wentworth).

They were all baptised at Attercliffe Chapel, also known as Hill Top chapel from its prominent location. The chapel, rebuilt in 1909 and restored in 1993, survives to this day, together with its graveyard of monuments to early Sheffield industrialists.

Woodbourn (House) stood on what is now known as Woodbourn Road in Sheffield, close to the Supertram stop of the same name. It had a variety of occupants after the Hartops, but is perhaps best known for its Sorby family occupants, including John’s uncle Henry Sorby (1790-1846) and perhaps most famously John’s cousin, Henry Sorby’s son Henry Clifton Sorby (1826-1908). Certainly a name with a face which is easily traceable!

Born at Woodbourn, H.C. Sorby was the only child of Henry Sorby and Amelia (née Lambert, 1797-1874), H.C. Sorby became a world-renowned polymath: naturalist, geologist, metallurgist and microscopist. His family’s wealth enabled him to dedicate his life to scientific pursuits, and many of his early geological observations and experiments on the formation and structure of rocks took place at Woodbourn and within its grounds by the River Don.

Well connected: family and business networks

Iron in the blood? John Hartop’s father Henry

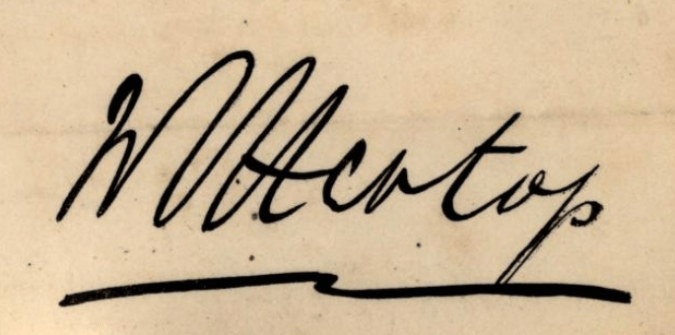

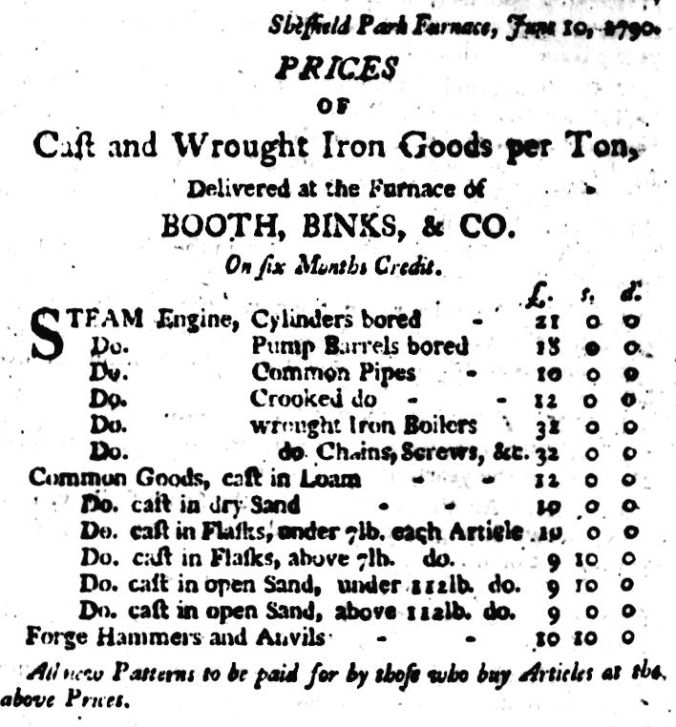

John was named after his grandfather, although he never knew him. Henry Hartop’s father was John Hartop (1745-1788) and he was one of the original partners of Booth and Company. The main partnership agreement had been signed on 1st June 1784, set to last for 63 years, taken from 25th March 1782, and consisting of 16 shares split amongst the original partners:

- George Binks (1724-1790) of Hall Carr in the parish of Sheffield, iron master – 4/16

- John Booth (1735-1797) of Brush House in the parish of Ecclesfield, iron master – 5/16

- John Hartop (1745-1788) of Mill Green, Brightside Bierlow, iron master – 4/16

- and William Binks (1720-1788) of Brightside Bierlow, iron master – 3/16

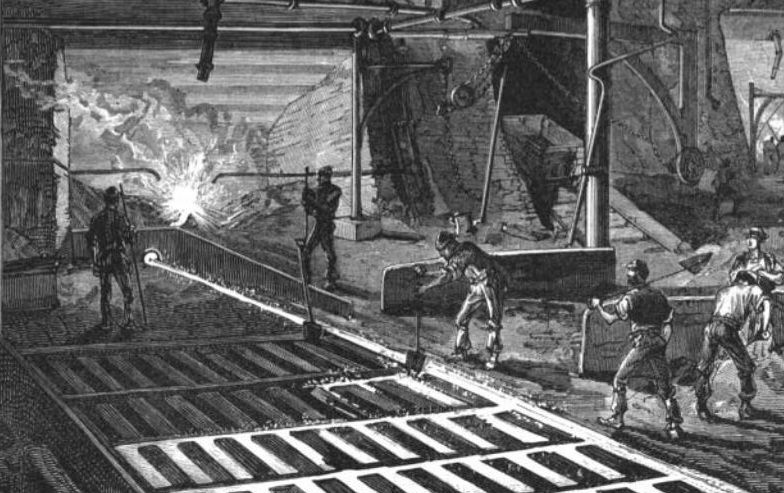

The partnership was formed to make iron, and forge it into bars and rods. The concern held leasehold properties at Brightside and Sheffield Park from the Duke of Norfolk, and worked an iron forge, slitting mill, rolling mill, tilt, a cutler’s grinding wheel and workshops at Brightside Bierlow, with three other cutlers’ grinding wheels and corn mill. There were also two other cutlers’ grinding wheels at Sheffield Park, where the company were about to build a furnace, which commenced work, or rather was ‘blown in’, in February 1786. Booth and Co. appeared to prosper, and a second furnace was added around 1806.

John Hartop senior married twice: first in 1770 to Hannah Crapper (1754-1783), daughter of William Crapper, a wheelwright; they had three sons:

- William Hartop (1771-1829, died in Pennsylvania, USA),

- John Hartop (1774-1809)

- and George Hartop (d.1829 purportedly in America).

Henry Hartop was born in 1786 to John’s second wife, Mary Binks (married in 1785). His mother Mary was the daughter of William Binks, one of the fellow partners in Booth & Co. Henry was just 2 when his father died in 1788, and his mother remarried in 1795, to William Littlewood (1765-1812) who also worked for Booth and Co., as well as having his own business interests.

William Littlewood and Mary then had children of their own:

- Mary Littlewood (1796-1873), who married Edwin Sorby in 1818.

- John Littlewood (1799-1868), who married Catherine Sheardown in 1829

- Anna Littlewood (1802-1868), who married Edward Sheardown in 1824 (Edward was Catherine’s brother).

Over time the original partners of Booth & Co. passed away, the heirs of Booth, Binks and Hartop, and their assigns inherited interests in the partnership shares, leading to some complicated legal transactions, and rather more potential beneficiaries than active participants in the business; something worsened by further intermarriage, probate arrangements, and not least the small matter of the collapse of Messrs Parker, Shore & Company‘s bank in Sheffield in 1843, which took Booth & Co. down with it.

A former partner in the bank, John Shore, foolishly allowed Booth & Co. to take large credit advances from the bank, amassing unrepaid debts of £64,000 (equivalent to £3.8M at today’s prices). But that is another story altogether!

Deep ties: John Hartop’s mother, Anne Sorby

Anne Sorby was the daughter of John Sorby (1755-1829) and Elizabeth Swallow (1761-1829). Her mother Elizabeth was the daughter of Richard Swallow (1729-1801) of New Hall, the proprietor of Attercliffe Forge after the famous Fells dynasty had established a successful Swedish iron importation and steel furnace trade between 1699-1762.

Anne’s father John Sorby, was a steel edged tool manufacturer and merchant, who gained success for producing very effective sheep shears and other tools which were sold around the world.

John Sorby and Sons, the earliest registered maker’s mark from September 1791- a fleece mark, or hanging sheep (from Robinson, J., A directory of Sheffield, J. Montgomery, Sheffield, 1797)

Two of Anne’s many brothers, John Sorby Jnr (1786-1861) and Henry Sorby (1790-1846) joined their father in the firm John Sorby and Sons, also joined later by their younger brother Alfred (1800-1860). John Sorby and Sons established the Spital Hill Works, near the Wicker in Sheffield, part of which still stands, although recently converted into apartments.

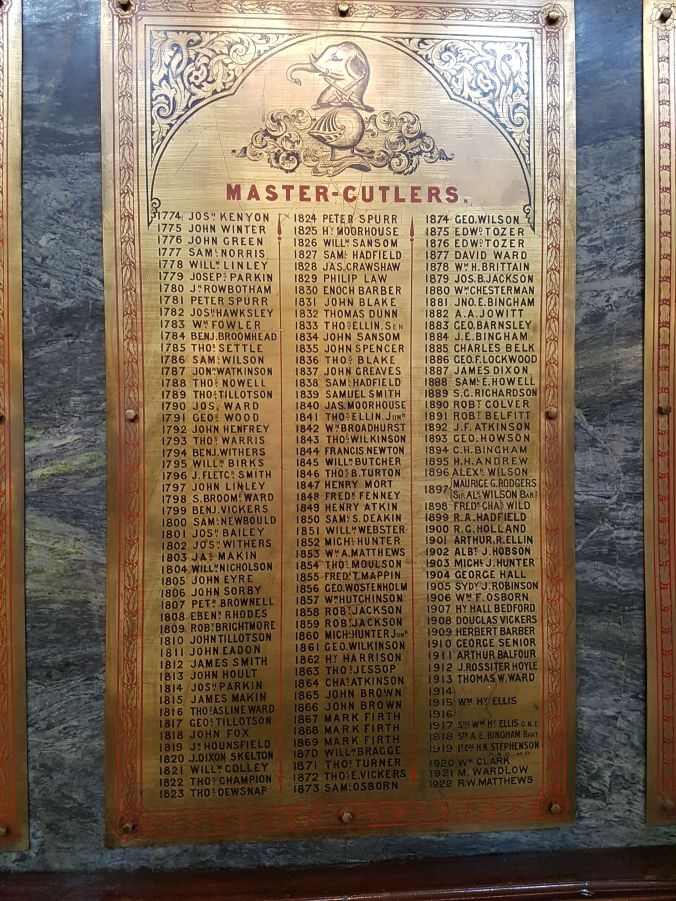

John Sorby himself rose to prominence just before Henry Hartop and Anne Sorby were married, serving as Master Cutler in the Company of Cutlers in Hallamshire in 1806.

It should be noted that the Sorby family’s connections to Sheffield and to the Cutler’s Company stretch back to the 17th Century, and the first Master Cutler. Several branches of the Sorby family established steel edged tool firms, with files, augurs and saws, and were active in commercial and civic life in Sheffield well into the twentieth century.

Connecting the dots, it is interesting, if unsurprising to note that John Sorby (Anne’s father) and William Littlewood (Henry Hartop’s step-father) were also business partners. From 1805 they established a large partnership trading as the ‘Sheffield Coal Company‘, sub-leasing the Duke of Norfolk’s coal estate around Sheffield from the estate steward, Vincent Eyre. The original Sheffield coal partnership included:

- Charles Nixon, of Walbottle, Northumberland, Coal viewer,

- William Littlewood, of Sheffield Park, Ironmaster

- John Sorby (Anne’s father), Sheffield, Merchant

- John Jeffcock, Sheffield, Collier (here meaning owner of collieries, not a miner himself!)

Until 1806, when Nixon left the company, later known as Littlewood, Sorby and Jeffcock. The Littlewoods further intermarried with the Sorbys when Edwin Sorby (1782-1864), a younger brother of Anne, married Mary Littlewood (1796-1873) the half-sister of Henry Hartop!

The Hartops at home: Rotherham and Hoyland

Henry Hartop really began his connection with the ‘family’ ironfounding firm Booth & Co, around 1807, progressing to become manager. His half brothers William and George Hartop were also active in the concern at different times as well as operating businesses of their own at Blackburn forge and Attercliffe steam mill, and working in London before heading to America in the 1820s.

Henry worked closely with his step-father William Littlewood, becoming a member and secretary of the Yorkshire and Derbyshire association of ironmasters, and he was appointed joint executor of his step-father’s will in 1812. William Littlewood died leaving a substantial estate valued at over £25,000 (roughly over a million at today’s prices).

On William’s death Henry became head of the family and was supposed to protect his Littlewood half-brother and sisters’ interests until they came of age. From 1813 he enjoyed the benefits of having a sixteenth share in Booth & Company, but by 1821 he had struck out on a new venture with his immediate family: taking out a lease from Earl Fitzwilliam of the Milton furnaces at Hoyland.

At that time Milton iron works had only just been given up by the giant ironfounding firm, the Walkers, of Rotherham. The Walkers were connected to the Booth family of Booth & Co. both by marriage, but also by longstanding business connections dating back to the 1748s when John Booth went into partnership with them in a steel works Masbrough, operated as Walkers & Booth.

They would have known the Hartops of old. Indeed, when Henry and Anne Hartop moved their young family out of Woodbourn, in Sheffield, they moved straight into Ferham, becoming tenants of Jonathan Walker’s grand residence first built 30 years earlier on the profits from ironfounding, making cannon for the Royal Navy.

The new partnership at Milton, in the township of Hoyland Nether, was known as ‘Hartop, Littlewood and Sorbys‘, and consisted of members of Henry’s wife’s family and his half-brother, all of whom could bring significant family wealth as capital to the concern. They took over the two active blast furnaces at Milton with:

- Henry Hartop, as manager

- John Sorby (Henry’s father-in-law)

- James Sorby (Henry’s brother-in-law)

- John Sorby, jnr (Henry’s brother-in-law)

- Henry Sorby (Henry’s brother-in-law)

- John Littlewood (Henry’s half-brother)

After some successful early transactions, including a spectacular contract for 2 chain suspension bridges in 1823, Henry set about renewing the rolling and slitting mills, building a new forge, and adding 3 metal helves with a steam engine, but this work ground to a halt in the summer of 1824 as Henry’s partners (his family effectively) became alarmed at the rising costs and insufficient returns. As a visiting ironmaster noted in 1825:

“Mr Hartop is a very scientific man but very expensive in the erection of his works”

Butler’s Tour amongst the Yorkshire and Derbyshire ironworks, April 1825

The iron trade was no longer the reliably profitable concern it had been during the long years of the Napoleonic Wars. In February 1825 they finally dissolved the partnership; Henry had the works to himself, but needed capital, so he rapidly entered into a new partnership with William and Robert Graham, trading as Henry Hartop & Co. (starting from June 1824).

The Grahams were London iron merchants, rather than ironmasters themselves, and wished to keep their names out of proceedings as they dealt with many ironmasters, but sought to secure direct access to supplies of pig iron.

NB pig iron was the cooled product cast from the molten iron ‘tapped’ from a blast furnace, so called from the analogy of a sow feeding piglets echoing a main stream of smelted iron being fed of to multiple rows of iron ‘pigs’.

Up to 1827 Henry’s family lived in some grandeur at Ferham, however things were going wrong in the second partnership at Milton; indeed, they had been going wrong in the financial affairs of Henry Hartop for quite some time. There were arrears to Earl Fitzwilliam for coal supplies, for ironstone deliveries, and rent.

In autumn 1827 William Graham took over management of the accounts of Henry Hartop & Co., although Henry continued to manage works operations until the Grahams pressed to end the partnership and rid themselves of Henry Hartop.

However, with no amicable agreement with his partners, the terms of the dissolution were referred to arbitrators. The final outcome, although later challenged by Hartop, was a severe loss; his half share and interest in the concern became the property of the Grahams. Time was up: in 1830 Henry Hartop was declared bankrupt.

Bankruptcy proceedings, started in February 1830 and rumbled on for years, right up until 1846, as the official assignees of the estate in bankruptcy tried to recoup money from the many business interests Henry was still engaged in, or the property, assets and annuities he had inherited, even if he had already had to auction off his household furniture. Thankfully, as we have seen, his wife and her family had independent means, and their children attained financial security themselves in their marriages.

Growing up in Hoyland

The Hartop children, Amelia, John, Helen and Ann Elizabeth, enjoyed a very privileged upbringing with domestic servants. Their parents were prominent members of the local community, especially in Hoyland where Henry Hartop regularly corresponded with and met Earl Fitzwilliam and his heir Lord Milton.

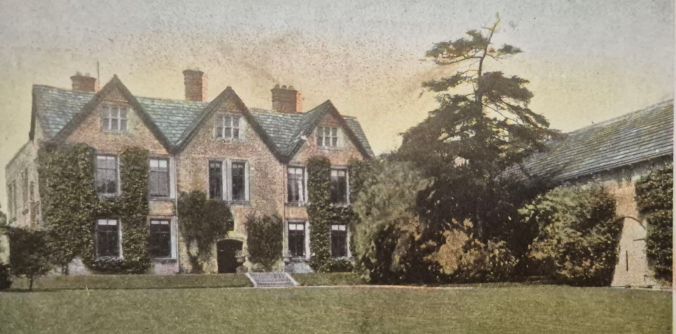

Around 1827, a lease was taken of Hoyland Hall, much closer to the Milton iron works than Ferham, but also a very visible come-down. This is where the Hartop’s children, John included, would spend much of their youth; it was the home they effectively grew up in.

From 1831 Henry Hartop was perhaps partly redeemed by being employed by the 4th Earl Fitzwilliam as manager of the Elsecar Iron works just down the hill from his ill-fated connection at Milton. Elsecar Ironworks had been established and previously run by John Darwin & Co. who themselves had gone into bankruptcy.

It was while managing the Elsecar Iron Works that Henry would encounter one of the most colourful characters in this story, the world famous inventor and engineer James Nasmyth (pictured below in an early photograph) who would go on to marry John Hartop’s sister Ann Elizabeth. Nasmyth diplomatically described the lot of the Hartops at Hoyland in 1838 when he first met the family and his future wife-to-be:

“Mr. Hartop having met with some serious reverse of fortune, owing to the very unsatisfactory conduct of a partner, had in a manner to begin business life again on his own account and although he had to reduce his domestic establishment considerably in consequence, there was in all its arrangements a degree of neatness and perfect systematic order, combined with many evidences of elegant taste and good sense which pervaded the whole, that enhanced in no small degree the attractiveness of the household.” James Nasmyth, engineer: an autobiography, John Murray, London, 1885, p.226

John Hartop steps forward

During these years the young John Hartop worked under his father at Elsecar, on behalf of the 5th Earl Fitzwilliam who had succeeded the 4th Earl in 1833. The iron trade was still rocky; Henry was still struggling to pay the wages, and money was being lost.

Despite the family’s move to Barnburgh after 1841, young John took over the management of Elsecar iron works himself. His father Henry eventually left Elsecar having run of of excuses and perhaps having exhausted the Earl’s patience. He sought employment elsewhere, beginning with Bowling Iron Works in Bradford in 1844-47, and later at Stanton iron works in Derbyshire, but he was ageing and no longer able to sustain the family himself.

John Hartop ran Elsecar Ironworks from his father’s departure up to 1849 when both Milton and Elsecar iron works were leased to the West Midlands ironmasters, the brothers William Henry and George Dawes.

John Hartop was making his own mark in the world: like many young men in the local gentry and aristocracy, he joined the volunteer yeomanry cavalry movement, serving as Cornet and, after 1854, Lieutenant in the 1st West York Yeomanry Cavalry. This provided regular contact with Lord Milton, later Earl Fitzwilliam who served as Colonel. It also underscored a love of horses, breeding and fox hunting which remained life long passions, however anachonistic it may seem to modern eyes.

John was retained on the staff by Earl Fitzwilliam after 1849, but employed on a reduced salary, overseeing the deep ironstone mining at the shafts at Skiers Spring, and establishing what would become the Earl’s own centralised workshops, the ‘New Yard’ at Elsecar (now Elsecar Heritage Centre).

Following the death of Benjamin Biram in 1857, John also took over as General Manager and Agent of the collieries, and was based at the Mineral Office at Elsecar. He was responsible for the extensive Fitzwilliam collieries at Parkgate and at Elsecar, with their canal and railway connections, a role in which he continued to serve under the 6th Earl Fitzwilliam, right up to his final retirement in 1886.

And so to Barnburgh

By the porch to St Peter’s church in Barnburgh, near to Mexborough, stands a prominent memorial cross, a grave to John Hartop (1815-1902) and his wife Mary (née Brook, 1824-1911).

John and Mary lived together at Barnburgh from the time of their marriage in 1862 when he was 45 and she 38, until their deaths: John died 17th March 1902, aged 86, and Mary died 28th November 1911, aged 87. John’s parents Henry and Anne Hartop, and his eldest sister Amelia, are buried in an earlier family vault sited next to John and Mary’s more modest grave.

John and Mary had no direct descendants, although the grave itself and the inside of the church bear testament to the affection of John and Mary’s nephews and nieces, and John’s contributions to restoring the church were long remembered.

Like his parents and grandparents before him, John had married into industry and wealth – Mary Brook was the daughter of Jonas Brook of Meltham, who established enormously successful cotton spinning factories. Despite the failures of Booth and Co., and of his father Henry Hartop, John Hartop and his wife Mary’s fortunes were very secure.

Why Barnburgh?

John’s parents, Henry and Anne had moved to Barnburgh in 1841 taking a tenancy of Barnburgh Hall. Barnburgh (also Barnbro, Barmboro, Barnborough, and various spellings!) was a relatively small and isolated rural village, on the hillside above the River Don, between Mexborough and Doncaster.

It would have been a peaceful spot, certainly in comparison to living amongst the smoke and noise of the ironworks, collieries and labourers as they had at Hoyland. The children had grown up now; John would be the last to marry.

Face to Face

So what about putting a face to his name?

In 1885, just before he retired from Elsecar, John Hartop attended a horse sale, known as the annual Yearling Sale at Doncaster. That year a remarkable subscription portrait was made, with people paying to be portrayed in a giant composition, based on photographs taken of each individual.

This enormous painting, now in Danum, Doncaster’s Museum and Art Gallery, gives us our answer, a face to the name: J. Hartop is there in the crowd:

Thanks to Nick Crouch and Heritage Doncaster’s ‘Changing the Record’ project in 2021 for helping to bring this to light.

This is an excellent account, which fills in some of the pieces I’ve been missing. I’m a Sorby descendant, although from a parallel line. The developments in iron and steel and coal made fortunes for some but miserable livelihoods for many. Because in the UK it has been so linked to military and economic interests, this sector’s pedigree is littered with boom and bust, and nationalisation eradicating orgins in business interests such as the Hartop’s and Sorby’s. Although the ghosts can be found in Rolls Royce, Aecom, NatWest and others. Another interesting aspect is the transition from capital (land and buildings) funded by and leased from the aristocracy. Sincere thanks to the author(s).

LikeLike

Hi Martin, many thanks for your reply. Would be pleased to add more links and information if you have them and which branch of the large Sorby family etc if you would like to, would be delighted to contact via: hemingfield.colliery@gmail.com

LikeLike