Staying on the front foot after weeks of catch-up activities, the Friends of Hemingfield Colliery arrived earlier than usual at the pit. Early, if not bright, but in good spirits!

Opening up for a brisk day of tidying, ticking off a series of smaller, but useful, odd jobs; the bits and bobs (or random tasks, depending on your point of view) which really need doing, but aren’t always the first priorities. Variety being the spice of life, it was a fun day and great to see volunteer efforts have real impact during the day itself.

A Gateway to new possibilities

Efforts began at the east end of the site, over by the pumping engine house where strimming and weeding and generally cutting back were definitely in order. With work to do inside and out of the site itself, it was time to open up the side gate and mosey on out.

Accompanied by the giddy bleating of nearby pigmy goats, the Friends and volunteers, revved up and cut back, taking down the excess grass and weeds which had shot up; 2021 definitely feels like a tropical growth year for the annals in that respect, with sunshine and rainfall feeding the unrepenting docks, thistles, nettles and grass.

Outside the gate, things were perhaps unsurprisingly messier: Wath road suffers from many a drive-by tosser (of litter) as well as the odd walk-by flinger of crap (figurative and literal). Removing the long grass by the old coal store revealed a mini ‘plastic harvest’ of bottles and rubbish. The mind boggles, but it is reassuring to see so many local people volunteering to pick litter, even if it is a pity it seems necessary.

Takeaway – if only.

On the subject of rubbish, summer holidays seem to accelerate the quantity appearing outside the pit gates and strewn down the road. We often see unwanted examples of wanton drive-by ignorance: discarded plastic wrappers, beer and pop cans; paper bags and cardboard boxes to name just a few lowlights.

The pretty green corridor down to Elsecar is sometimes besmirched by the thoughtless and lazy actions of a few. The origins of the rubbish require no great archaeological insight to pin down, with fast food and cheap alcohol brands plastered across the packaging. In the face of indifference it is heartening to learn about efforts of local people to maintain the canal, and working with the local authority to keep paths and alleyways clear.

Local improvements

In the next 6 months we also hope to see the exciting results of new work underway under the aegis of the South Yorkshire Mayoral Combined Authority (formerly known as Sheffield City Region)’s Active Travel Fund, Phase 2.

The Elsecar Active Travel Link is a scheme being taken forward under Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council, to improve the public rights of way and the Trans Pennine Trail, promoting walking and cycling routes between Elsecar Park, Elsecar Heritage Centre and Cortonwood Retail Park.

The work, which is expected to be delivered by Spring 2022, is currently taking further feedback from local community members via a survey.

The final details, costs and benefits will be finalised and reported on in the near future, but include road safety changes to Wentworth Road and Wath Road as well as widening and resurfacing works to the Trans Pennine Trail.

Smothering heights: vine and ivy

A brief glance at the past – September 2015 – serves to illustrate the power of nature and specifically of ivy and Russian vine growing all over the old Cornish pumping engine house, now Pump House Cottage.

It’s easy to forget the scale of the challenge in cutting it back and keeping the growth down when the Friends finally secured ownership of the Pump House Cottage, thanks to National Lottery players via the National Lottery Heritage Fund‘s support for our Hemingfield’s Hidden Heritage project, we have been able to make a substantial start to restoring, linking-up and opening out the site for visitors, even if the precautions and privations of Covid19 lockdowns have delayed and disrupted some of the planned activities to date.

Rampant nature

The unhappily named ‘mile-a-minute’ plant can look pretty in its dark reds and greens, but is also a real threat to vulnerable structures over time as well as having a suffocating effect over windows, vents and rooves.

Back to the present day (2021), the growth challenge remains; ivy grows and the vine has recidivist tendancies, so the work continues on all sides of the building!

Wheely high

An irregular, but necessary task required the attention of the crew at the main winding shaft headgear. Checking the owlbox and doing some minor maintenance and checks whilst up there. A quick check on the condition of the mobile winder wheel’s condition showed it to be in great shape, with well lubricated bearings, the wheel rotated freely.

Stepping stones

Finally, in an inspiring example of youthful elbow grease, regular volunteer Mitch painstakingly cleaned the stone steps from the upper to the lower levels.

Steadily picking, brushing and scraping away the muck, moss, weeds and accumulated gunk, some pretty smart stonework began to be revealed.

Looking cleaner and brighter, this effort makes the steps safer and more presentable to site visitors as well as bringing a welcome lift to thenwider crew who trudge back and forth through this busy stairway. A lovely job.

Distinguishing the best from the rest – Colliery day tripping, 1859

Departing the site in August 2021, one is bound to think of Summer Holidays, and sunny escapes to sunnier climes. With the Covid-19 pandemic still swirling around, thoughts of getaway holidays have tended to focus on the local, the regional, and mainly the intra-national. No bad thing. Discovering the joys of this fair isle is nothing new, especially when traveling by rail, as this glance into the past will show…

Joining a nineteenth century excursionist, journalist John Hollingshead (1827-1904), we offer a brief journey to a lost country, a day-trip to the Barnsley coalfield, specifically to the Lundhill, Edmunds Main, and Oaks Collieries.

“Finding myself in Yorkshire at an hour when I usually rise from the perusal of my morning papers, I am naturally led to ask myself what purpose has brought me there. I knew, before I started, that my journey had something to do with coal mining and the coal trade, but I am induced to search further and inquire again. I find that the directors of the Great Northern Railway had consented that, from the 1st of July, 1859, the produce of each of the various South Yorkshire collieries shall be sold with the name of the colliery, and unmixed with any other coal. The owners of the best coal regard this as such a boon that they have resolved to celebrate this separation of qualities by a train of pleasure to the “three pits,” and free passes are issued to a wide circle accordingly. Behold me – who know no more of the mysteries of the coal trade than others, who like to burn good coal, when they ‘ can get it—at Doncaster, then, one hundred and fifty-seven miles, by rail, from London, as the first stage in my train of pleasure to celebrate the separation of the qualities.”

John Hollingshead, “Two Trains of Pleasure”, All the year round. A weekly journal conducted by Charles Dickens with which is incorporated Household Words, vol.1, No.21, Saturday 17th September 1859, p.493 [author not attributed in original publication but later acknowledged and reprinted]

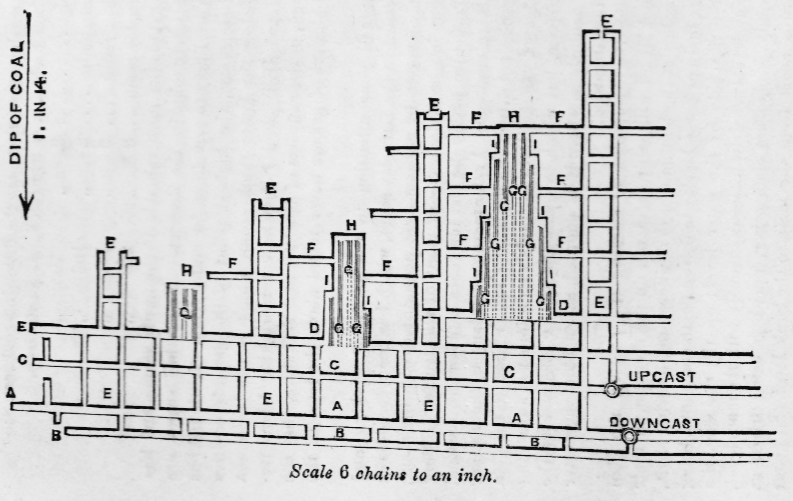

Lundhill Colliery

“The visitors who are assembled to celebrate the separation of the qualities, rush up a grimy ladder onto a grimy platform, and look down the smooth brick side of the pit’s mouth. At their back is the engine-house, where the engine draws up or lets down the chain which supports the cage; and at their side, to the east, is the ventilation shaft – a chimney that runs parallel to the descending shaft, and terminates at the bottom in a furnace. This furnace is never suffered to go out from the hour when it was lighted, as long as the mine is in active working, and in need of air… It consumes full an hour to let down the mass of visitors to the bottom of the pit. They take their places eagerly in the cage, like people who are anxious to get into a theatre, and they are sent down the hole into utter darkness at the rate of about eight miles an hour, and in parties of eight at a time”

John Hollingshead, “Two Trains of Pleasure”, All the year round. A weekly journal conducted by Charles Dickens with which is incorporated Household Words, vol.1, No.21, Saturday 17th September 1859, pp.493-4

“I took my place in the cage in front of a pale-faced gentleman, who looked as if the signal for letting us down was the signal of death to him, and he was perfectly aware of it. Not a sound was heard, nor the whisper of a voice, as we glided down the perpendicular passage…

When we had descended with giddy speed about two-thirds of the pit’s shaft – a distance of about one hundred and fifty yards – a sudden check took place, in order to let us down the remaining seventy yards with greater care. The effect of this check was to cause an illusive sensation that the action of the machinery had been reversed, and that we were ascending even more rapidly than we had come down. Wild thoughts of utter destruction – impending danger – the intelligence of something wrong being discovered below – passed quickly through the minds of the silent, breathless human cargo, and there was not an adventurous excursionist in that cage who did not wish himself well out of it. A few seconds of painful reflection, and instead of the welcome daylight being seen once more, a sudden shock was felt – the whole structure had suddenly touched the bottom of the shaft, and the travellers were dragged out of the cage and over a box ledge by rough and unseen hands, to stand in the bewildering darkness of the Lund-hill pit.”

John Hollingshead, “Two Trains of Pleasure”, All the year round. A weekly journal conducted by Charles Dickens with which is incorporated Household Words, vol.1, No.21, Saturday 17th September 1859, p.494

Hedley ‘ The Lund Hill Colliery Explosion. A Lecture’, Lectures delivered at the Bristol Mining School, 1859, p.132

After a public celebratory meal in Barnsley, the visitors returned to London King’s Cross via Doncaster, arriving after midnight.

Stepping out

Back in 2021, readers seeking similar undergound adventures in Yorkshire can do no better than head to the fabulous National Coal Mining Museum for England and book on to the Underground Tours.